|

by Goh Cheng Fai Zach

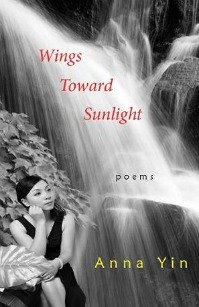

Anna Yin, Wings Toward Sunlight, Mosaic Press, 2011. 80 pgs.

Reading Anna Yin's Wings Toward Sunlight can be like having a religious experience if you open yourself up and allow the words to carry you where they may. Maybe this is why she starts the book with this quote from Emily Dickinson—"The soul should always stand ajar, ready to welcome the ecstatic experience"—so that readers will approach her poems with their own souls standing ajar, ready to experience her world. Here they will find a landscape where the inner-self meets the outer world, where the imagination meets reality, where Emily Dickinson meets Li Po and where simple things like bread and toasters, windows and mirrors and cups of green tea can convey profound truths. They will also discover a world which is not full of frenetic movement but is instead calm, contemplative and introspective and encourages a mood of revelation and enlightenment. Yin's poems, which never exceed a page in length, are always delicately and carefully layered. Her work has been described by Tammy Ho in the A Cup of Fine Tea section of this publication as "concise exploration[s] of the moment; a modern interpretation of the kind of classical Chinese poems, in which a specific scene, thought or feeling is condensed and captured in the most economic way." There is much left unsaid in Wings Toward Sunlight. This economy not only leaves much for the reader to interpret, but also enhances the sense of foreboding that haunts much of Yin's work. Reflections and mirrors permeate the collection. In "Twilight," where "a water lily/in her own petalled reflection,/rippling in crimson,/vanishes into the dawning light," we get a sense of a water lily letting itself be overtaken by the light of dawn. In "Rainy Night," a man makes an agreement with a mirror, represented by blooming roses on the window sill that witness the events of the rainy night of the title. In "The Wall," the speaker orders thirty-one new mirrors but "refuse[s] the one Plath's old woman/bent into," a reference to Plath's "The Mirror." The reference is carried further in "Why I Carry You, Mirror." Here, the speaker addresses her reflection in a looking glass, asking if it agrees with what "they say": that she looks more at the mirror than the fire, and that she is more like Plath than Dickinson. The glass remains silent, with "Plath swallowed within." Such imagery conveys a feeling of heightened self-awareness—reflection in its other sense—as well as a reminder that the reader is an observer to the events happening within the poems. In Yin's poetry, there is a meeting of both Chinese and Western ideas. In "Snake," she uses the Chinese "legend of White Snake" and the biblical story of the forbidden fruit to relate her feelings about her abandonment of a pet snake. She confesses her actions in "church," using "a language too pure for her tongue" and The snake spiraled up,

as if to catch the last

apple dangling in the air.

The lines clearly allude to the biblical story of Eden, where the serpent tempts Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. However, they also recall "The Legend of the White Snake," where the snake is also a symbol for temptation, a temptation for love that goes against nature, in this case, the speaker 's love for the snake she is forced to abandon. Yin's poetry also uses everyday items and events in ways that, like some of Plath's confessional poetry, are infused with deeper meaning. In "Bread and Toaster," we see a slice of bread tell a toaster of its longing for them to be together, only to be treated with silence and rejection. Later, the slice of bread has its wish to be connected to the toaster fulfilled, but is immediately eaten as toast. A similar sense of hopelessness caused by inevitability is seen in "Still Life," where the speaker mourns for some apples because "Either they face the knife/or wait to decay." In "The Flowers in my Vase," the flowers' helplessness towards their fate becomes a metaphor for the speaker's own life and wait for love, the implications of which she only realises as she smells the blooms for the first time. In the closing poem, "Winter Night," the speaker transforms an international phone call with her lover into a spiritual experience of renewal. The book closes with the image of the lovers' words "settl[ing] as seeds, left to tell---"; their words do not provide an ending but instead a sense of possible renewal and new experiences, an echo, perhaps, of Dickinson's entreaty for us to leave our doors open to new experience. In "Winter Night," Yin reminds us of how endings do not always signify finality but can also signify beginnings: Last night over the line, I heard you again.

Through blue waves, I was listening.

Breezes come and go, Sunflowers wither and grow.

Your words settle as seeds, left to tell---

|