|

by Jennifer Wong

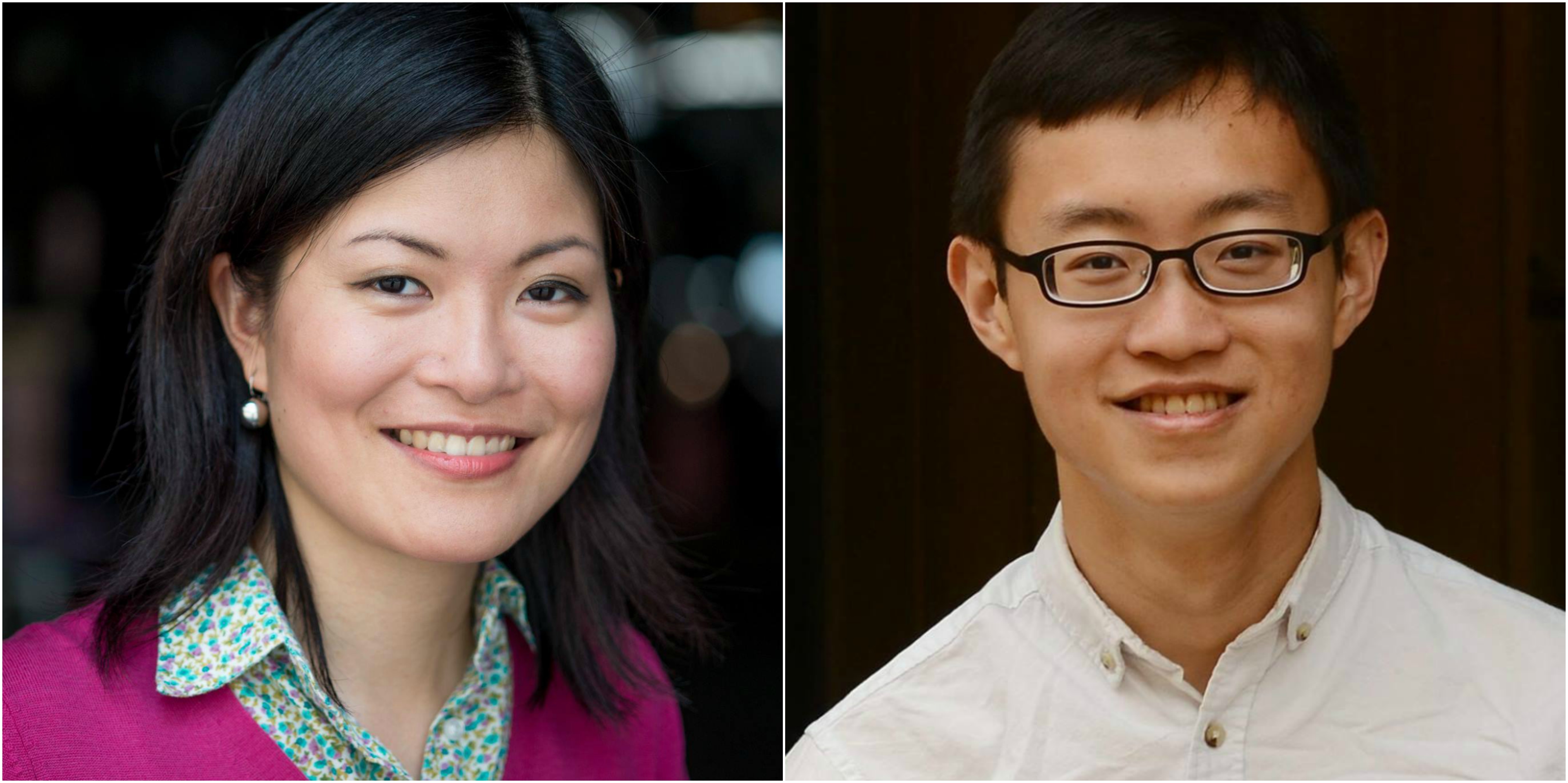

Jennifer Wong and Theophilus Kwek Theophilus Kwek is the author of four volumes of poetry, most recently The First Five Storms, which won the New Poets' Prize in 2016. He spoke to Jennifer Wong about identity, the meaning of home and the influences on his work. Jennifer Wong: As a poet who has lived in different "places," how do you see the meaning of home and being away? Do you think it has a temporary or permanent impact on your work? Theophilus Kwek: I'm responding to this interview at home in Singapore, having completed three years in Oxford in one programme and about to embark on one more, in another. Having left Singapore in the first place with an obligation to return, I have never let myself stop seeing Singapore as "home," since I know that will only make it harder when I have to come back. What has happened instead is that I allowed myself to rethink and reframe what "home" means. Before I left, "home" was a catch-all for where all my loves and loyalties lay. It was a social concept (my family, friends, teachers and immediate community were all in one place), as well as a political one (I felt a special and non-rational obligation to the nation and its representative state). Three years on, I would probably hold to a far more nuanced idea of "home" as a set of social ties capable of grounding a sense of belonging and a set of inherited and invented narratives that one must wrestle with and remake. Crucially, also, one must "call it home": the act of choosing a place and naming it as a site of belonging is what gives it its special validity to the individual—a validity that no other community or governing body should compete for or deny. Personally, I think of both Oxford and Singapore as "home," in different ways: they represent different senses of belonging, different narratives of life and, perhaps, different selves—both versions of which I've learnt to be true to. That change has probably had a permanent impact on my work. My recent writing is, at the same time, both less and more rooted than before. It refers less to one place as especially identity-giving, or having an exceptional claim on my obligations. At the same time, it's more ready to engage with traditions and tales that make up a "place." It's more willing to belong. JW: How do you see your identity as a writer and, in particular, as a Chinese writer? Do you see yourself as a writer of Chinese ethnicity? Should ethnicity be remembered or ignored when readers appreciate your work? TK: I have always believed that good writing comes from being a whole, honest person. For many writers, this will mean responding perhaps not directly to colour, but to the complex of assumptions and traditions in one's cultural inheritance. Of course, in situations where colour, or interactions on the basis of colour, become visceral or inescapable (something that occurs, far too often, in violent and unacceptable ways), there is a natural and necessary call to respond in writing. But part of being a writer of any culture or colour, I think, should involve some response to, or interrogation of, the whole cultural package that we live and receive. It also involves a critical assessment of how we, as members of (or migrants into) any cultural system, interact with those who identify with others. On a personal level, this means that I cannot escape being a "Chinese writer" if I am to bring my whole self to my craft. Growing up in Singapore, where I had, for the most part, a secular, bilingual education, I've found myself (consciously) grappling more often with the linguistic, rather than the cultural aspects, of being Chinese. At the same time, it is hard to avoid noticing the ubiquitous presence of Chinese cultural systems, symbols and social structures pervading what is ostensibly (and proudly) a multicultural society, and I think my more recent academic and creative work seeks to reckon with that. That is simply and necessarily part of being a thoughtful writer in society. So to me the more interesting question is not whether I am a "Chinese writer," but what exactly that means. No two Chinese writers have the same experience of being "Chinese," no two Chinese writers share the same ethics of responding to their heritage—and rightly so. Our landscapes of speaking and writing are made richer by the difference. I see my part in the equation as writing in and writing out, an experience of being Chinese that refuses the easy categories of "mainland" or "overseas," "first-" or "third-generation," "standard-" or "dialect-speaking" and "native" or "immigrant," as well as a response to elements of a Chinese heritage (from the stories I've heard as a kid to a sense of social paranoia and conservatism) that I think of as good and also true to my self, place and time. What this means for readers is probably that my writing is as much me as it is Chinese. The "Chineseness" of the work is certainly an important source of seeking and knowing. But I'd like to think that the self that does the searching, transformed not only by its cultural baggage but also by its milieu and beliefs, warrants equal if not greater consideration. JW: Do you feel you have to choose between Western poetics and Asian poetics, and why? TK: No. There is plenty of diversity among both "Western" and 'Asian' poetic theories and traditions, representing but some of the many ways in which (and the many reasons why) people write. Occasionally ways of writing that are traditionally thought of as "Western" or "Asian" are more similar than at first sight: both schools, for example, have a strong history of landscape writing—dealing with similar associations and processes—that cultural purists on both sides would probably seek to claim as their own. The truth behind such similarities lies partly in the fact that global cultural flows are nothing strictly new: the annals of world history are littered with encounters and collaborations that take place between traditions or represent the movement of artistic and literary styles across borders. That said, I suppose the question still remains: do I feel I have to choose one set of poetics over another? The answer to that is also no. Despite being in some senses (as I've explained above) a "Chinese writer," I could not possibly stick to Chinese poetics—especially when life demands that I engage on a daily basis with the English language and its (global) histories. Thankfully, poetry is a living thing that allows for the different poetics we inherit to be merged and remade: forcing future analysts, I hope, to apply new labels to ours! JW: Have you ever wanted to write in Chinese? Does it matter? TK: The only creative piece I have ever written in Chinese and had published was a short story that I (defiantly) wrote in place of a school essay, which failed all the classroom requirements but made it into an interschool anthology of young fiction! Unfortunately, I was too young then to appreciate the unique qualities the Chinese language could afford to a writer, and now—having spent several years in an English-only environment—I'm confident enough to translate from Chinese but not write in it. I am not sure if it matters. Personally, while I know that greater fluency in Chinese and the confidence to write in it would doubtless add to my writing in English, full bilingualism is a rare privilege. In that sense, I am content with my own creative writing journey. It doesn't really matter to me either way in terms of self-definition: I see my writing as coming from the person I am now—pretty fluent in English and less so in Chinese—and not moving towards some ideal in which, as a Chinese person, I "should be" able to speak and write in Chinese. My less-than-perfect Chinese attests to who I am as a Singaporean-born, English-educated Chinese person, and I'm comfortable with that: in fact, there are just as many (if not more) interesting points of tension and cultural crossover that I can investigate. JW: How do you see the nature and development of Asian-themed anthologies? Would you like to see any change in the approach towards representing these voices? TK: I think such efforts are helpful to the extent that they chronicle the reception history of a set of cultural symbols left over by war, revolution, migration and other upheavals. Asian writers—defined, in the broadest sense, as writers associated by birth, citizenship, family or choice with any country on that continent—are writing back today after what has been one of the most tumultuous centuries for nearly all Asian nations. There has rarely been a greater degree of cultural flux within any given century for many of the continent's proudly established and long-held traditions. With this cultural flux comes some of the most exciting writing and translation produced in the world today: take the PEN-award-winning work of Han Kang and Sawako Nakayasu in the past year, for instance. So yes, I'd say Asian-themed anthologies are a valuable site of collaboration and documentation. The sad truth about anthologies in today's creative environment is the inadvertent pigeonholing that results from grouping writers under any identity label—whether that's ethnicity, cultural heritage, gender or age. It becomes harder to see writers as the whole persons represented in their work and, to a certain extent, shared concerns have become labelled as sectional ones. We risk choosing a prism through which to view some of our most exciting writers when, really, what they need most is to be showcased alongside the work of writers from as many other traditions as possible. The best "Asian" anthologies, I think, take concepts that are traditionally seen as "Asian" and invite thoughtful, creative contributions from writers of all backgrounds and identity choices: these help to blow established cultural stereotypes out of the water and reshape closed symbols into open ones. Read "Uriah" by Theophilus Kwek here. |