|

by Michael Tsang

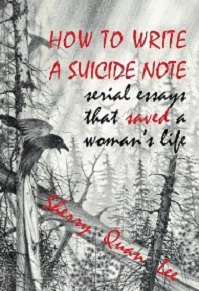

Sherry Quan Lee, How to Write a Suicide Note: Serial Essays that Saved a Woman's Life, Modern History Press, 2008. 91 pgs.

As Sherry Quan Lee's poetry collection, How to Write a Suicide Note, unfolds, the reader discovers how eager the poet is to share her experiences, voice and notions of writing as therapy with anyone who is willing to listen and treat her with respect. This fine book offers a personal dialogue between the poet and the reader. At times, I felt like Sherry (the works are so intimate that I have opted to refer to her by her first name) was speaking directly to me, and I hope my review will reflect my highly personal response to her work. At first blush, the title of the collection is confusing and shocking—is the writer encouraging people to take their lives? It's only when one gets to the subtitle, Serial Essays that Saved a Woman's Life, that it becomes clear that Sherry is sharing her poems (or essays, as she calls them) to save other lives. Divided into five sections, each starting with a "suicide note," the book reads at first like a soliloquy. The poetic voice can be sometimes lively, sometimes sly, sometimes melancholic. This change in voice is arguably disorientating at times, and it may be hard for readers to follow the thoughts as they shuttle from one line to another. But the merit of this kind of writing is that there is no holding back; everything written down is straight from Sherry. The first poem, "Suicide Note Number One," begins with determination: "Dear Self-Esteem,/Today I am writing to destroy the lack of you." These engaging words begin the poet's journey to regain her self-worth and self-respect, a journey in which she uses a variety of literary forms (you have just read the start of a poem presented as a letter) and voices. At times in the collection, it seems there is no boundary to her experimentation. In "Suicide Note Number Four," for example, Sherry adds a chunk of dry newspaper-style testimony on social mobility in the middle of the poem, followed by these unconventional lines: My mother said don't tell anyone that you are __________

How could I?

I didn't know I was __________

any more than I knew I was __________

Silence. Invisibility.

The point, needless to say, is not what the blanks represent, but the blanks themselves. Indeed, as "a Black/Chinese woman passing for White" in America, the poet likely experienced being invisible to and silenced by other people. When this suppressed voice finds utterance, the blanks become the embodiment of both the emancipation of a suppressed voice and suppression itself. The best poem of the collection is the second last one, "That's Where She is Now." For the first time, there is not an "I" on the entire page, and the poem goes beyond the first-person narration of the other works, offering immense imagination and reflection: In the back of his house there are blue

trees, thirty feet tall, thick

like history. The spruce

cast shadows aqua blue,

baby green. Seeped in mystery.

Each tree a pyramid. Sunlight

slinking around another

untrimmed day.

Here is Sherry's true poetic talent on display. Between each comma or full-stop is a concise image, but the short lines and enjambments keep the poem rolling, revealing more as the reader's eyes dart from left to right. For Sherry (and perhaps for all of us who work with words), writing is her therapy. The book is not only a guide to saving lives; it is also a guide to writing, a book for writers. Sherry is not afraid to share her writing process, knowing full well that the process itself is a form of healing, as is shown in "Avoidance, About Writing": as a first draft simmers I continue to revise

scrutinize the tone, the rhythm – the meaning

draft number two is ready to print

before draft number one has finished printing

each new draft allows me to live vicariously

clutching draft number two I disappear

to smoke a cigarette and read aloud

The subject of writing also appears in other poems, where there are passages challenging the rules in creative writing and sending up the pretentiousness of academic communities. What this book has taught me, however, was not about writing, but about reading: it is not always a wholly pleasurable experience; sometimes you have to work at it. A common and handy phrase to use when reviewing a poetry collection is "you will be able to connect with these poems," or "you will find things in common with these poems"—as if the works have no value if we cannot connect personally with them. Relatively few people in this world, I imagine, share Sherry's experiences of having an African mother and a Chinese father, and fewer still might, as the psychotherapist whose testimony appears on the jacket suggested, have also gone through some kind of therapy. I do not think any one of us will completely understand all the struggles she has undergone. However, this does not mean Sherry's collection does not have any value at all. What I see in this collection is Sherry striving to have her voice heard, to reveal herself and to heal. To reciprocate Sherry's efforts, I think I have the responsibility to try my best to comprehend, feel and understand her work. Each poem asks probing questions that set me thinking. For the reader there may be repetitions, a sense of déjà vu, but I think patience may be in order; for Sherry, these might express entirely different emotions or experiences which she wants us to understand. How to Write a Suicide Note showed me how to approach unfamiliar styles and experiences, and when I closed the book, I wanted to applaud Sherry for her courage and guts. I only hope my reading has done her justice. |