|

by Michael Tsang

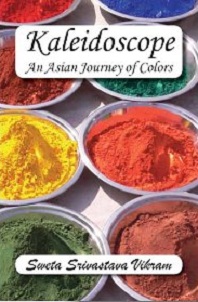

Sweta Srivastava Vikram, Kaleidoscope: An Asian Journey of Colors, Modern History Press, 2011. 20 pgs.

As any of you who frequently visit Cha will know, for each issue the editors work hard to find a suitable cover image and match it with a suitable background colour. Colours may seem neutral, but they often mean much more. Not only are they used for aesthetic purposes, but they may take on emotional meanings and each of us may cling to certain shades in different periods of our life. In the chapbook, Kaleidoscope: An Asian Journey of Colors, Sweta Srivastava Vikram explores the relationship between the stages of our lives and colours by recounting the life of an Indian woman through different hues. Different cultures associate colours differently. White may symbolize purity in the West but be used in funerals by the Chinese. Yet, for Vikram, there is not necessarily any logic behind the symbolism of a specific colour. The meaning of each shade for an individual is influenced by the interplay of culture and personal experience, an interplay which is explored throughout the poems in this collection. One finds in Kaleidoscope, for example, a feisty backlash against assigned gender roles in Indian culture. Matrimony is particularly suspect, as it is an institution that incarcerates a woman's agency and dictates her fate. For the poet, the colour brown, and marriage, is rancid: She hears him decry

as she blends into dusk

the same color as his eyes

the soil his ancestors rest in

the chocolate his sister devours

the carnal desires he adores

[…]

A bitter almond,

her earthliness

echoes the lines

of her putrid life. ("Rancid Brown")

The italicized lines illustrate Vikram's skill at fluidly connecting four different images with one colour. In another poem, "Cryptographic," Indian bridehood is condensed into a "voluptuous dot on the forehead-beseeching destiny"; through the deliberate italicization of other phrases in the work like "to erase identity" and "to mark the prey," one understands that the redness of this dot can mean more than luck or danger. The remaining poems are mostly about birth and childhood and death. In the poems about youth, a retrospective poetic voice is often unmistakable. In "Innocence Comes in Pink," even as a six-year-old girl is infatuated with her pink innocence, she is also clearly aware that teenage girls often go "boy crazy." She takes pride in the fact that she is not tainted by "worldly pleasures" and compares herself with a stallion. These are not entirely the thoughts of a six-year-old girl and one can perhaps see the recollection of a more mature voice slipping in. Yet, there is a kind of sincerity in Vikram's writing; readers can easily detect some genuine emotions and experiences as she sew colours and lives together. As the persona enters old age in "Ageing with Beige," this tone of recollection is replaced by a sense of defiance against age: I appear alive. You can smell the flesh and stream of red

flowing through my goblet-shaped heart, but take a peak

inside the mystique, I am crumpling – emotions in a knot.

The clustering sounds and the varying phrase lengths demonstrate Vikram's awareness of the different paths of life: some longer, some shorter. For three stanzas, the poem works in this format, until the last one, where it ends crisply with an internal rhyme—"I am sixty, not dead; not beige, color me red"—as if the persona is still crying out with the vibrancy and spiritedness of youth. A series of five poems meditate on death as the chapbook comes to a close. If life is "a hue of experiences," then death would be its opposite and exist only in greyscale. Lamenting that "iridescence holds no value," the persona first turns grey "like ethics and skies of London" in "Time Traveled." Darkness then descends, and the persona makes one last attempt to recall her mother's wardrobe: I hid under mama's black sari,

dark like the night, so the silk

unpredictable as the serpent's slither,

could caress my concluding desires

and soothe my mortal fire as I wind up

my journey with colors. I am ready for my

next destination – the time when I die. ("Reflecting on Iridescence in Mama's Wardrobe")

Yet, there is no fear of death, for it is just the "next destination." What is important to Vikram, it seems, is the multicoloured tones of life and the ability to paint them in poetry. The collection ends with a few haikus, one of them proclaiming that white is our destiny, and another munching on words like "dries" and "halts"—no sad feelings, just a simple curtain to close not only a chapbook, but a life. Kaleidoscope: An Asian Journey of Colors is rich with imagination. Each poem is neatly polished and most associate one colour with an aspect of an Indian woman's life. Vikram could have perhaps gone further with this conceit. Just as each shade is ultimately a mixture of different hues, no period of life can be strictly defined by one event, and as such, perhaps she could have explored how colours combine, recur or expand during different periods of life. This would have fitted a chapbook titled Kaleidoscope. But as it stands, the book achieves its mission to delineate an Asian journey, with flying colours. |