|

by Abigail Cheung

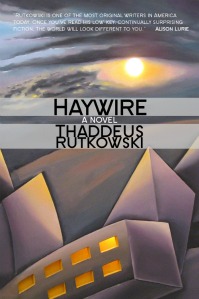

Thaddeus Rutkowski, Haywire, Starcherone Publications, 2011. 298 pgs.

Haywire, Thaddeus Rutkowski's third novel, offers edgy and artful insights into the life of a young, nameless, biracial American male. Comprised of forty-nine "flash" stories—each no longer than eight pages—it highlights key moments in the narrator's journey from childhood to parenthood, taking its readers on a whirlwind tour of emotions stirred by abuse, race, hate, addiction and fetishes. The results are mixed. Written in sharp, terse prose, Rutkowski's individual pieces often push boundaries in a simultaneously refreshing and disturbing manner. However, the book's segmented structure means that Hawire does not always feel like a coherent whole. The book is divided into three parts, each covering a section of the protagonist's life. In Part I, Rutkowski narrates key events from his childhood and his relationships with his Polish-American father and Chinese mother. The six-page opening vignette, "In Cars," contains five concise, drama-filled scenes. In the first, Rutkowski focuses on the boy's alcoholic father, particularly his unsavory cooking, unusual parenting techniques and obsession with communist ideals. In the second, the author relates an encounter between the narrator and a boy next door that is suggestive of molestation. In the next two sections, Rutkowski uses conflict to allude to issues such as family's dysfunction. In the first of these, he recounts an argument between the protagonist's parents about family finances, and then moves onto a verbal exchange between the boy's brother and a stranger that threatens to escalate into physical violence. In the closing scene of "In Cars," the writer narrates a dream in which the protagonist wants, but is unable, to help a child. The end of the story leaves readers with an overwhelming sense of the boy's impending doom. The compact but jarring manner in which Rutkowski narrates "In Cars" is characteristic of his writing in Haywire. One benefit of this style is that the emotions in each story, including those in "In Cars," are pronounced and self-contained. However, because each of these comprises only snippets of the protagonist's extremely varied life—he goes from building homemade bombs to making stage props, from being hooked on marijuana to being addicted to sex, from being abused by his father to becoming a father himself—the narrative feels disjointed when viewed as a whole. While Rutkowski's style allows individual stories to stand on their own, it does not enable them to form a particularly coherent novel. Rutkowski's characterisation is also problematic, and his protagonist seems unusually detached. In "Hobbies," the narrator's father invites the boy to comment on his paintings. The protagonist first notices his sister's silhouette in one piece and then "the back of her nude body" in another. Still a child, he is unaware that he should or even can confront his father about his voyeuristic tendencies. He therefore resigns himself to not knowing "if my father had worked [on the nude portrait of my sister] from memory, from photos, or from real life." In "Hobbies," the narrator's detachment puts readers in the awkward position of being made to feel that they are inadvertently condoning the antagonists' actions against the girl. Over time, this type of detachment may make readers deeply uncomfortable and ultimately hinder their ability to empathise with the protagonist. Although the narrator matures during his college experiences in Part II, as well as in portions of Part III, in which he moves to another city, for the most part, he remains frustratingly passive. He allows peers to call him "chink," "Jap" and "Bali Ha'i" rather than clarify that he is Polish-Chinese-American. He mistakes women who smoke pot with him for women who are in love with him. When a story he presents at a reading flops, he "figures he could store [the 100 leftover copies in his closet] indefinitely." Perhaps most egregiously, at one point, he goes to jail for a crime that he did not commit without so much as a word of protest. Yet for all his passivity, the protagonist is also reckless. He starts "smoking himself silly," having unprotected sex and orchestrating dangerous sexual manoeuvers such as "suitcasing." The protagonist does not take control of his life until it is almost too late. More than two thirds of the way through the book, he is still almost completely resigned to his addiction-filled, loveless, fatalistic life. It is only in "Recovery is for Quitters" that Rutkowski offers readers hope once again. While unable to immediately hold down a steady job, convince others to trust him, love someone or be a father, the narrator eventually begins to toy with these ideas. Ultimately, they inspire him to find love, become a father and transform into the type of character that readers desperately want him to be—someone with whom they can empathise. The protagonist's transformation, while drawn-out, highlights Rutkowski's remarkable ability to navigate through a litany of difficult, dark subjects. Exemplary of art created for art's sake, Haywire, while rough and raw, is also a welcome, worthwhile read. |