|

by Feroz Rather

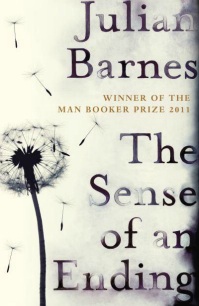

Julian Barnes, The Sense of an Ending, Random House, 2011. 160 pgs.

Is writing fiction a way to supplement memory, a retrospective filling of the gaps when one fails to remember clearly or at all? That seems to be the answer implicit in the poetics of Julian Barnes' most recent novel, The Sense Of An Ending. Like many other fictional narratives, for instance, Jean Paul Sartre's Nausea—no comparisons invoked though—this one is also conscious of its own fictionality. Much later in the novel, the narrator, Tony Webster, a retiree in his sixties, tries to remember a place and the people who inhabited it, all rather important to him in his youth. The "order" and "significance" are lost in the stream of his memory but some "long-buried" details resurface. Tony, curious about other details, takes the easy recourse to the Internet: On a whim I Googled Chislehurst. And discovered that there'd never been a St. Michael's church in the town. So Mr. Ford's guided tour he drove us along must have been fanciful—some private joke, or way of stringing me along. I doubt very much there'd been a Café Royal either. Then I went on Google Earth, swooping and zooming around the town. But the house I was looking for didn't seem to exist any more. In this search, Tony is trying to recall memories from his university years in the 1960s. On a weekend during school vacation, Tony is invited to visit his girlfriend's family in Chislehurst in Kent. Her father, Mr Ford while introducing the young man to the town, draws his attention to Saint Michael's and Café Royal and the names stick in Tony's memory. But now, more than thirty years later, what does this failure to corroborate their existence implicate? To a great extent and successfully, it lends a meta-fictional aspect to the story, and in a way makes it more distant from the narrator's "reality." The conscious implanting of doubt about what one thinks really happened in the past not only pushes the story further from the reader (and consequently invests her more in it), but also points to the writer's need to revisit and fabricate in and around the holes in memory's fading blanket, a necessity central to the creation of all autobiographical fiction. And since biographical details confirm that Tony resides more in the realm of imagination than the writer's real life, through Tony's reminiscences, one expects a richer and deeper level of complexity to unfold and be illuminated. To get to Chislehurst, Tony takes a train from Charing Cross in central London which runs "out on the Orpington line." At the station, he meets Veronica, who introduces him to her father, Mr. Ford. Tony finds him "large, fleshy, red-faced," and marvels how such a "gross" man could have fathered such an "elfin daughter." Later, while showing him the room where he is to stay in the upper story of that "detached, red-brick, tile-hung house, in one of those suburbs which have stopped concreting over nature," Mr. Ford tells him to pee in "a small plumbed-in basin." To Tony Mrs. Ford, Veronica's mother, also appears unlike her daughter: "a broader face, hair tied off her forehead with a ribbon, a bit more than average height, she had a somewhat artistic air, expressed through colourful scarves, a distant manner, the humming of opera arias, or all three." It's left to the reader to picture Veronica, who constantly eludes Tony's memory, by inversing these features: a lean face, untied hair, probably loosely and beautifully falling over, average height or a bit less than average, a somewhat inartistic air. (The last trait, though, might not fit into the overall scheme the mysterious woman she is supposed to play.) Finally, there is also "a healthy, young" Brother Jack, who "likes to laugh at most things" and whom Tony finds "easy to read." During his stay there, Veronica, whom Tony is still in the process of getting to know and understand, or misunderstand, "withdraws into her family to assess his social and intellectual credentials." The initial unease results in Tony's constipation and things seem to ease off only— not the constipation though—when towards the end of the visit, Veronica, in front of Jack, fiddles with his hair in the living room and later kisses him goodnight. Later, Tony takes Veronica to meet with his two oldest friends, and a later addition to their secondary school group, Adrian Finn. Of the three, it is Adrian Finn, a "tall, shy boy," the one who challenges the other three intellectually and morally, that emerges as a compelling character in the novel. Adrian is a constant presence in Tony's life, even after his early death. He is the yardstick against which Tony measures the depth and dimensions of his own self, a mirror in which he combs the last grey hairs on his balding head, the other against which he effaces himself and expresses the ordinariness of his being. Adrian Finn comes from a "broken home," because his mother has walked out of it early on, but he doesn't seem to be affected by it, which makes Tony and his friends believe that happiness does not reside inside the family. Adrian is the one who has read Albert Camus and Fredrick Nietzsche, and he believes that "principles should guide actions" against the "hedonistic chaos" ascribed to by their "book-hungry, sex-hungry, meritocratic, anarchistic" gang. While responding to their history teacher during a lesson in which the Serbian gunman is being scrutinised for triggering the First World War, Adrian puts forth many different forms of historical explanation to challenge the notion that we can truly make sense of the past: We want to blame an individual so that everyone else is exculpated. Or we blame a historical process as a way of exonerating individuals. Or it's all anarchic chaos with the same consequence. It seems that there is—was—a chain of responsibilities, all of which were necessary, but not so long a chain that everybody can simply blame everyone else. But of course, my desire to ascribe responsibility might be more reflection of my own cast of mind than a fair analysis of what happened. After meeting his friends, Veronica leaves Tony for Adrian, who is attending college at Cambridge. Tony is not completely remorseful because Veronica has been an enigma to him, and he still doubts on some level whether she was even his girlfriend. What does perplex him about Adrian and Veronica's relationship, however, is Adrian's eventual suicide and its causes; what leads him to slit his wrists in a bathtub. When years later, the narrator Tony, now a divorced father of a middle-aged daughter, is mysteriously bequeathed £500 pounds from Veronica's mother, seeks out Veronica again. It is a mystery that Tony wants to solve, and one that Barnes wants his readers to engage with. But beneath this Tony wonders what could have been the reason for Adrian's suicide, the same Adrian whose reasoning had always seemed lucid and convincing at school. And it's in this sense that the novel suffers greatly by not treating the theme of suicide to its fullest, by not even risking any dark Dostoevskian revelations. As the narrative is written from Tony's perspective, the reader has no direct access to Adrian's consciousness; indeed, one of the main themes in A Sense of an Ending is the way in which Tony misconstrues the past as he is unable to know what people are or were thinking. As such, the narrative is structured in a way that Adrian figures as an odd and recurring reminiscence, an adumbration of a character. In the end, we are left only with the philosophical reasoning of Adrian's publicly available suicide note—"Life is a gift unsought for, and every being has a right to return what he never asked for"—and a mysterious equation from his diary. Add to this, Adrian's hinted at, but largely undeveloped fascination with Camus, a philosopher who addressed the issue of suicide in The Myth of Sisyphus and in The Rebel, and the whole affair amounts to Barnes nonchalantly pointing the tip of his finger from a safe distance toward that universal mystery, that raging and serious debate of to be or not to be. Here, somehow, I think of some of our greatest writers, Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf and more recently David Forster Wallace, who after a lifetime of intellectual engagement, gave into what Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali sums up in his one line poem, "Suicide Note": "I could not simplify myself." When it comes to recent fiction dealing with memory, some scintillating examples come to mind. Colm Toíbin's short story "One Minus One" is a musical elegy of a son remembering the death of his inconsiderate mother: The moon hangs low over Texas. The moon is my mother. She is full tonight, and brighter than the brightest neon; there are folds of red in her vast amber. Maybe she is a harvest moon, a Comanche moon. I have never seen a moon so low and so full of her own deep brightness. My mother is six years dead tonight, and Ireland is six hours away and you are asleep. Such is the melancholy eloquence of this passage that it encompasses the entirety of an ocean, and the ripples of grief can be felt across the Atlantic. Similarly, John Banville's The Sea (Booker Prize, 2005) with a deeply personal voice and attention to landscape, achieves a tenebrous lyricism while an old man confronts the death of his wife and remembers the profound follies of his childhood: She too, my Anna, when she fell ill, took to taking extended baths in the afternoon. They soothed her, she said. Throughout the autumn and winter of that twelvemonth of her slow dying we shut ourselves away in our house by the sea [...] The weather was mild, hardly weather at all, that seemingly unbreakable summer giving way imperceptibly to a year-end of misted-over stillness that might have been any season. Yet Barnes chooses restraint, fiddles with the ideas from too far a distance. This results in characters which barely move beyond drab, archaic typologies and fail to challenge or thrill. Although the end of the novel does suggest a possible explanation for Adrian's eventual suicide, I still felt like Barnes missed an opportunity to delve more. What is achieved is a contained narration, garnished with witty phrases like "philosophically self-evident," "a susurrus of awed mutterings," etc., striking a wryly funny tone. What is also achieved is the Man Booker Prize for the year 2011. What is lost, however, is the chance to further complicate and probe the mind of Adrian, to illuminate life and literature with a fresh streak of artistic or intellectual light, to organically theorise about the complexities of psychology and memory in the manner of a nimble Nabokov, a reflective Levi, a sagacious Sartre, to create some shimmering stones in the necklace of novel thought. |