|

by Tshiung Han See

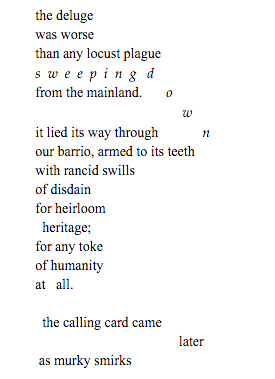

Andrew S. Guthrie, Alphabet, Proverse Hong Kong, 2015. 88 pgs. Vaughan Rapatahana, Atonement, Flying Island Books and MCCM Creations, 2015. 124 pgs. Lines of prose find themselves in between lines of poetry. We've arrived at a new stage in human development. "Alphabet" is the name of one of the biggest companies in the world. If code is language, then the world runs off of millions of lines of language every day. From cradle to grave, we are immersed in language. Our consciousness is partly defined by it. And yet, there are still experiences that language is barely able to touch. Alphabet is a collection about the "vagaries of failure," a mixture of narrative and lyrical free-verse poems. The cover cuts the title in half: the first half, "Alph," is upside-down, while the second half, "Abet," is right-side-up. And so you could not be blamed for thinking that the collection was actually called "Abet." The book's thematic focus on failure would suggest that this potential misreading is intentional—reading can be seen as a form of abetting—we will read intentionality into everything. But Guthrie, here, is perhaps giving us something more: perhaps a clue that poetry demands a reorientation of perspective. Defamiliarisation is at work here. Betelnut becomes "dusty, bug-chewed pulp." A brain is not just a brain. It is a hard drive. And thoughts are files. The cloud is also the brain. Guthrie uses line breaks to control the flow of information. All poets do this. But Guthrie's method reminds me of Wallace Stevens, especially in his use of enjambment. At best, he turns stuttering into a political act. At worst, his line breaks are pauses, breaths, units of meaning. (In "Unsorted," his lines are often longer than the page will allow. Could this betray a reluctance to break the line and create meaning? Or could this be an example of "the letter" taking over what is "left of the lyric," as expressed in one of the poems? We must read intent into every line break.) Collections that take the alphabet as an organising principle tend to be encyclopedic—think Louis Zukofsky's A or Ron Silliman's The Alphabet. Does Guthrie's collection aspire to similar heights? Yes, but it's a very specialised encyclopedia. It's an encyclopedia of failure. After making its distaste for manifestos abundantly clear, the collection ends with a manifesto, "kill all the poets," ringing with the same reasoning as "eat all the children." An equivalence is drawn between failure and writing, especially the writing of poetry. Failure ultimately emerges as a rejection of power, "the power to refuse our consent," as Primo Levi said. Alphabet is about the failure of poetry. That is, about the failure of writers in service to poetry, about the winnowing of writing into a single form, the failure of poets to the poem, about the world's failure in service to poetry, about how power is constructed, about how literary movements are cults of personality. It is about the recovery of irony. And it is very funny. *** Atonement is a perfect-bound, pocket-sized book, big enough to fit in your breast pocket, in the rough position of your heart, or the back pocket of your cargo pants, in this way resembling a phrasebook. Although it is a smaller than Alphabet, it is longer and feels larger. We know from Rapatahana's bio that he's spent time in the Philippines, New Zealand and Hong Kong. Tagalog, Maori (whenever he wants to say "New Zealand," he uses its Maori name, "Aotearoa") and Cantonese feature in many poems. These snippets of other languages may distance readers, especially readers who live in the thick of cultural homogeneity, but they give the poems highly personal textures. These are textures that would be impossible to achieve any other way. A different reader, one sensitive to other cultures, may even be drawn in. You can tell Rapatahana likes to play with sounds. All poets do, but Rapatahana especially here, hits Hart Crane-like heights, and sound and meaning dovetail. In one poem, Rapatahana likens a poem to an animal so wild it's impossible to trap it inside "the alphabet cage." Returning to the sounds of words is one way of taming the wild animal, but never trapping it. Rapatahana plays with the shape of words as well as the sound of them. "I'm trying to get across the way things are," he says, "through typography, rather than just straight English." We see this in the poem "saint tomas deluge, 2012," in which "sweeping down" stretches out and descends, acting out the thing it describes"

Rapatahana lets words rise and fall like staircases on the page. Words are stretched out like exhaling accordions. (At one point, he inserts gaps in the word "connection," to illustrate what is lost, or else the word is a train, pulling into the station. Its letters are carriages and they all haven't come to rest yet.) "He patai," about a question, is shaped like a question mark, turning the punctuation mark itself into a conversation between a line and a dot. The book's title is perhaps an allusion to Ian McEwan's 2001 novel about love and forgiveness. Feelings of loss are present here, and they are expressed plainly, like in the poem "some days," and the lack of artifice is shocking and powerful. But Rapatahana doesn't seem to be atoning for anything. Instead, these poems seem to be exercises in tone. Rapatahana is clearly having loads of fun in these poems, even when he's angry. Playing with language is fun and you never need to put away your toys. His range of expression is certainly wider than a poet who sticks to conventional typography. He cares about what the poem looks like on the page, and I like that he cares, because not many poets do. |