|

by Karen Fang

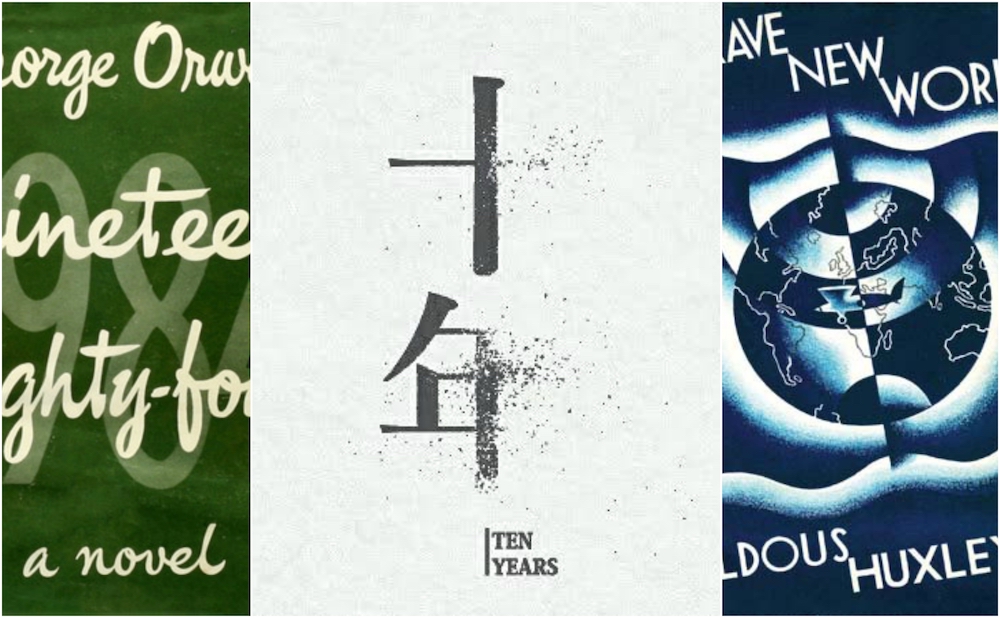

In January, George Orwell's dystopian classic Nineteen Eighty-Four shot to first place on Amazon's best-seller list in the United States, crowning a sudden rebirth of interest in the cautionary tale that had been brewing for months. As much commentary noted, sales were particularly high in the US, the UK and Australia—all Western nations currently riven by divisive social politics—suggesting that this renewed interest in a novel about a charismatic demagogue spouting misleading evidence and trafficking in xenophobia had arisen out of a desire to use fiction to understand the contemporary world. As someone who regularly teaches Nineteen Eighty-Four amidst scholarly research on literary and cinematic representations of surveillance that encompass both East and West, I would like to raise several other issues both implied and complicated by this Orwellian resurgence and its perceived resonance for Western countries. First, although most of the current interest in Nineteen Eighty-Four emphasises a totalitarian future prophesied by the current climate of race hatred and economic disenfranchisement, it is also worth noting that such an analogy represents a stark reversal in longstanding notions about consumer abundance and the "end of ideology" shaping modern surveillance. For decades now, surveillance theorists from Gilles Deleuze to James Rule, Mark Andrejevic and Gary T. Marx have been showing how the consumer opportunities available through digital technology and other conveniences of modern life have reconstructed surveillance as a condition in which individuals willingly surrender privacy and access in exchange for perceived benefits. This shift marks a stark change from the paranoid images of the threat of containment and physical punishment with which surveillance is commonly identified in canonical works by Orwell and historian Michel Foucault. What is chilling, then, about current readers' interest in Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is not only that it reflects the paranoia and economic desperation of the contemporary sociopolitical climate but also that, in doing so, it recognises a sharp regression from the prosperity and borderless mobility that we previously enjoyed. Not insignificantly, the corresponding literary model commonly invoked by surveillance theorists to name this alternate surveillance society is Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, a novel actually published seventeen years before Orwell's and with which Orwell—who had studied under Huxley at Cambridge—was clearly engaged. The respective positions of this debate are too complicated to rehash here, but a second insight worth raising about both works is that although race, ethnicity, nationalism and other forms of cultural and geographic difference play important roles within both novels, perhaps one reason that Orwell's novel is gaining renewed influence now is that Nineteen Eighty-Four explicitly portrays Asia as bogeyman and pawn in the militarised rhetoric of fear in which Big Brother traffics. Throughout Orwell's novel the declining white empire of "Oceania" is always at war with East Asia or Eurasia—in fact, a particularly macabre moment in the novel occurs when a professional orator charged with inciting crowds abruptly changes mid-harangue from vilifying one enemy to the other. As Orwell describes it, "it was almost impossible to listen … without being first convinced and then maddened." As a description of political rhetoric and its use in mobilising consent, Nineteen Eighty-Four thus presages the ever shifting, fill-in-the-blank scapegoating of ethnic, racial and religious others that fuels so much of our post-9/11, anti-immigration and anti-China hysteria. In stark contrast to the complacent, euphoric consumers doped up on sexual promiscuity and recreational drugs in Brave New World, Orwell's canny prophecy of the fear and antipathy in contemporary surveillance society shows how "Hate continued exactly as before, except that the target had changed." Thirdly, although China is specifically mentioned only a few times in the novel, one reason perhaps that Nineteen Eighty-Four has such resonance today among Western countries is widespread anxiety regarding imminent Chinese eclipse. At this moment, after three decades of relentless Chinese growth, we are all aware of the country's extraordinary political and economic power; further astonishing is the fact that China has achieved this ascendancy while unabashedly deploying Communist practices of party privilege, informational opacity and repressive tactics of eliciting compliance. Nineteen Eighty-Four, thus, is specifically compelling in the context of the rise of contemporary China. Although Orwell developed his fictional projections of socialist excesses on Russia, the 1949 novel's images of mass labour organisation, uniformed anonymity, group persecution and self-critique proved uncannily prophetic of Mao's Cultural Revolution. Moreover, although prosperous postmillennial China has moved far beyond that terrible history—and indeed some portions of the Chinese population are enjoying rapid increases in their standard of living—almost any Chinese citizen or China watcher today is well aware of the government's active role in censoring facts and manipulating the free flow of opinion. The widespread ignorance among contemporary Chinese youth of the Cultural Revolution or of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests are two glaring examples of the country's efficacy in implementing Orwellian "Ministry of Truth"-type information distortion. Thus, although little of the recent commentary on Nineteen Eighty-Four's current popularity among Western nations has yet acknowledged this China connection, the contemporary Sinophobia presumably underlying this interest reveals both Western insecurities regarding declining power and the uncanny similarity between current domestic policies and the belligerent fear-mongering associated with the East Asian Communist state against which Western powers historically have defined themselves. Hong Kong author Chan Koonchung's superb novel The Fat Years (published in Chinese in 2009 and English in 2011) offers a compelling glimpse of such a modern China where problematic history has successfully been erased from common knowledge, and it is with such alternate sources of literary and artistic consideration of surveillance society that I broach my fourth and final point. Both Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World portray literature as a volatile, powerful agency, equally capable of subversion and indoctrination: Shakespeare is banned in both novels, and both works' protagonists are knowledge workers employed in propaganda who suspect that an alternate literary production could be the means of undermining entrenched power. Current popular interest in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a resounding affirmation of this humanist claim, but as The Fat Years shows, global culture is rich with diverse other works that may illuminate Orwellian insights far beyond surveillance society's canonical Western texts. Cinema in particular should be recognised as a vital resource within this archive. Although the telescreens and "feelies" in Orwell and Huxley's respective novels suggest ambivalent or critical positions regarding the moving image, Huxley's more stylistically experimental novel also includes moments of impressionistic stream-of-consciousness whose montage-like imagery suggests a traditional medium reinventing itself along new modes and formats in search of ever more powerful ways of soliciting affective response in order to incite political change. Thus, while the recent return to Orwell's classic bespeaks a heartening resurgence of art and literature in an austere and repressive world where such engagements seem increasingly less possible, it is important to remember to look beyond regressive Western navel-gazing to consider contemporary works from throughout the globe that can also offer insight into these conditions, both within the West and about the rising powers with which the West increasingly now must contend. The 2015 Hong Kong film Ten Years, for example, consists of five self-contained stories that each imagine what life might be like in Hong Kong a decade into the future, as the Chinese government's strengthening hand—evident in recent events such as the abduction of dissident booksellers and the unilateral divesting of elected legislators critical of the government—only continues to entrench. Not surprisingly, the film was the object of direct attack by the Chinese government, which was widely thought to be the reason for the film's quick disappearance from Hong Kong theatres (despite sell-out audiences); and later, the Communist party instrument, the Global Times, dubbed Ten Years a "thought virus" and the Chinese government cut the Mainland broadcast of the 35th Hong Kong Film Awards during the climactic moment when Ten Years was named Best Picture. Movingly, though, in organised backlash by civic culture against this authoritarian censorship, Ten Years then precipitated an equally politicised counter-surveillance response, as the filmmakers worked with activists, educators and community leaders to screen the film for free at various locations throughout the city. Conflating film viewing with townhall-style assemblies often capped by post-screening discussions with the filmmakers themselves, these events urged audiences to view the dystopian imagery unfolding onscreen as cautionary tales for civic engagement and against political passivity. In the indelible words of Ten Years' concluding epigraph, the question of "too late? [or] not yet?" applies to all societies confronting an increasingly Orwellian future of discipline, surveillance and social control. Ten Years was in production when the "Umbrella" protests erupted in late 2014, and at a time in world history when anger is so rampant that communities from the First to the Third World are constantly spilling into streets in organised civic protest, films like Ten Years attest to the continuing power of literary and visual art to offer insight upon our changing world. More than a half century after Orwell's original vision, Nineteen Eighty-Four remains the canonical source text of global meditations upon surveillance society (it has even been translated into Chinese!). Yet with the economic and technological shifts that have been transforming politics and popular culture since the mid-twentieth century, even if Western readers correctly sense a tightening of government power and a freezing of individual agency that marks a stark turn away from the consumer freedoms of the past several decades, it is short-sighted to limit that inquiry to only the past Western canon. As Ten Years and The Fat Years show, new works and media from outside the Global North offer valuable insights into contemporary society, comparable to or even exceeding those found in longstanding Western surveillance classics like Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four. While American, British and Australian readers seek guidance in the great works of their past, they might also find more or better insight in contemporary works emanating from the Sinophone, China-dominated future. |