|

by Karlo Antonio Galay David

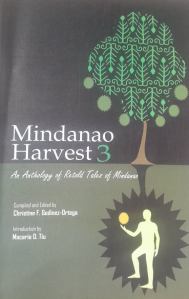

Christine Godinez-Ortega (editor), Mindanao Harvest 3: An Anthology of Retold Tales of Mindanao, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 2014. 95 pgs.

The third instalment of the Mindanao Harvest series features folk tales from the different indigenous tribes of Mindanao, retold for a more general readership by writers and academics. The style, approach and quality of the works, therefore, varies widely among the individual stories. The collection’s introduction by Macario Tiu touches on the underlying challenge of rewriting folk tales: the concerns of ethnography and creative writing may be different and are often contradictory. Ethnologists in principle transcribe and translate a piece of oral tradition as loyally to the source as possible, and this often leads to works that may be of great anthropological value but difficult to appreciate as literary works. In his book on fieldwork, anthropologist Harry F. Wolcott makes a distinction between “ethnography-as-art” and “ethnography-as-craft.” What sets these two apart is artistic license: whereas the “ethnographer-as-artist” understands the principles of the art and is free to break or challenge them, the “ethnographer-as-craftsman” is expected to adhere to the conventions of academic production. For me, the presence of the word “retold” in the collection’s title implies that its concern is less ethnographic and more literary. As such the works may be checked cursorily for cultural authenticity, but the bulk of its scrutiny must be through the lens of creative writing. Some of the more successful stories in the book are the origin legends from Zamboanga by the late Antonio Enriquez, from Cagayan de Oro by Zola Gonzalez Macarambon, the Maguindanaon by Jaime An Lim and the B’laan by Macario Tiu. Enriquez’s “Legend of PulangBato” dramatises quite effectively what must have been an origin story as short as a few sentences—framed quite charmingly as a tale told by an aunt. Macarambon’s origin of the name of Cagayan is a cautionary and quite beautiful tale against hubris. Tiu’s rewriting of a B’laan tale transcribed by Maria Vinice Organiza Sumaljag is an amusingly absurd depiction of man’s ingratitude and how it is used by the B’laan to explain natural and human phenomena. It is evident that these writers found very good original material, and they needed to do very little to make it generally appreciable. These origin stories are strongest as children’s tales and wouldn’t be too well received by a more mature readership (with the exception perhaps of Macarambon’s and Tiu’s tales). Among the collection’s best stories are brushes between the human and the (often fantastic) natural that are the foundations, really, of magical realism. This is the case with the very well written Maguindanao legend of the princess who can talk to butterflies by Cyan Abad-Jugo, the Bagobo origin legend of the durian by JaybeeArguillas, Theresa Padilla Abonales’ tale of Raga and the pearls and the wonderful legend of the Sultan sa Agamaniyog by the book’s editor. Arguillas’ Bagobo origin legend is really less an origin legend and more of a brush with the supernatural, portraying two fantastic scenes: the swallowing of the sun by Minokawa (a recurring legend among Philippine cultures about the solar eclipse) and the Beowulf-cum-kuzunoha revelation of the identity of the hero’s vengeful wife. The charm in Godinez-Ortega’s story lies not in its fantastic premise (like Abad-Jugo’s Maguindanao princess, her eponymous Sultan can talk to animals) but in the very human experience (spouses learning about love and trust) the story portrays. It even has an amusing image of a goat trying to get oranges reflected on water. Perhaps where Godinez-Ortega’s Meranaw tale could be improved is in developing the wife’s psychology—her sudden threat to kill herself feels arbitrary and out of the blue. One of the two best stories in the collection is also Meranaw (it seems the Meranaw are great storytellers), this time by Sittie Pasandalan about a mosquito picking a fight. The charm of this short, humorous story lies both in its deliberately anticlimactic ending and the absurd repetition that is used to build it up. The mosquito’s increasingly long, repetitive descriptions have an amusing oral quality—one can actually hear this story being told aloud! It is raw, unabashed entertainment with all the absurdities afforded to fantasy to that effect (tying it up quite subtly with the insight of how absurd pride—maratabat—can be). Merlie Alunan’s rendition of a battle scene in the Manobo epic Ulahingan may seem as absurd and inaccessible as Halili’s Bukidnon stories—perhaps even much more so—but as one reads it one realises that its absurdity can only be deliberate. Then one is reminded that this is an epic, in which logic is best suspended to appreciate the piece. And when one does so, what emerges from the “Siege of Nelendengen” becomes rich and layered allegory. It is full of Manobo cultural idiosyncrasies—Dumiwatag Ayamen hides his knives in the air and polishes his shield with the sexual secretions of his wife—but these serve to highlight the story’s universal themes of wanderlust, war-thirst, the love of home, the greatness of age against youth and the singular spirit that runs on both sides of the timeless tension between remembering the glorious past and moving forward to seek more glory. The episode—perhaps like the whole epic—is absurd in a poetic, almost lyrical way, the identities made fluid by the frequent change of names. One of the best stories in this collection, the “Siege of Nelendengen,” contains the spirit of Joyce, Beckett, Ionesco and Artaud, and more recently of the Japanese animation auteur Kunihiko Ikuhara. It is unfortunate that some stories in the collection are not as well-written as the others. The problem seems to stem from the authors’ hesitation, if not inability, to treat the material creatively. They fail to explore human psychology, or the spiritual impact of the fantastic experiences in their source narratives. The result are stories that are either bland or absurd. Such is the case with the Bukidnon stories of Servando Halili, Jr. and Carmen Ching Unabia, and the Tausug stories of Rita Tuban. All three happen to be academic researchers. Unabia’s “How the little boy Juan married a princess” is dryly written, with the author failing to develop the potential psychologically complexities of the source material. Tuban’s short origin legend of the mountain Bud Dajo has little movement and ends with an anticlimactic non-sequitur that could have been slightly remedied had the author explained why the discovery of Princess Baud led to the name “Bud Dahu.” Her “Salsila of the Prince Salikala” is rich in storytelling potential—what with the possible tension between the brothers Alimuddin Han and Salikala, as well as the poignant episode of the carabao fight, a tale bearing striking resemblance to the Minangkabau origin legend—but unfortunately it remained undeveloped. Halili Jr’s two short stories of Taibun and Daugbulawan are by far the least successful in the collection. The source legends are not only badly treated (wasting so much possible psychological and interpersonal conflict), they are also made difficult to access by technical terms that the author does not bother to explain (I was at a loss as to what a buklug was). The project of Mindanao Harvest 3 does not succeed in all of its stories, but where it does, it does so by highlighting the charms peculiar to myth and legend, bringing back the experience of wonder at sitting down and hearing a fantastic, often ridiculous but richly human story being told. Despite the unevenness in the quality of writing, this anthology is a very fulfilling read. |