|

by Stephanie Studzinski

❀ Audrey Chin, Nine Cuts, Math Paper Press, 2015. 102 pgs.

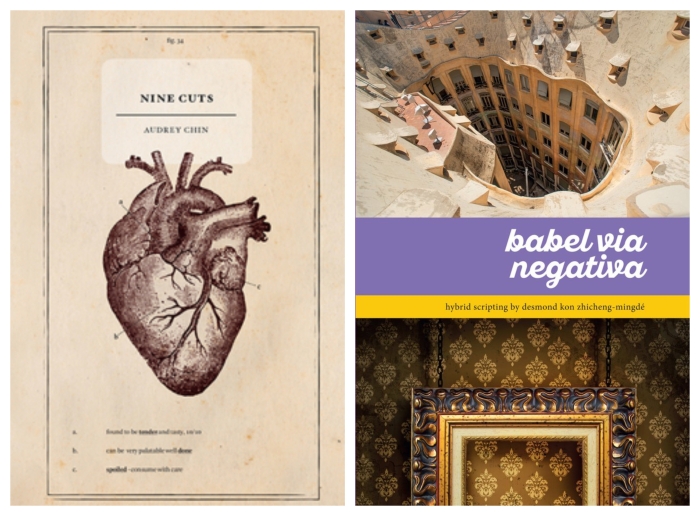

❀ Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé, Babel Via Negativa, Ethos Books, 2015. 176 pgs. Never judge a book by its cover—unless it is Audrey Chin’s Nine Cuts. The unique cover reveals much about the book: it features a vintage anatomical drawing of a heart with three parts being defined: a, b and c, reflecting the best culinary usage of each part. “a” is tender and tasty while “b” is best cooked well done and “c” is apparently always spoiled regardless of one’s culinary ability. This categorisation also acts the framing device for the book which offers nine stories or “cuts” of love: tender, done and spoiled. The book’s overall thoughtful layout and minimalist design subtly add much to the experience. For example, the frontispiece, end paper and section pages are solid black with minimal, if any, white text which feels reminiscent of a blade passing before the reader’s eyes as the “cuts” are revealed. Three of Audrey Chin’s books have been shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize, including Nine Cuts which is a unique and wide-ranging exploration of love and vulnerability that explores the many emotions we refer to under the umbrella term “love.” This ranges somewhat uncomfortably from cannibals seeking new quarry to the “love” present in domestic violence. Chin as a Singaporean author does much to reflect the ethnic and class diversity of Singapore through the wide range of stories and experience she represents. In fact, what I find most impressive about this collection is the diversity of experience and voice Chin conveys, and the way each story unfolds. Each story is carefully crafted to slowly unravel around the reader enveloping them into the narrative and, just as it is fully realised, quickly dissolve, paving the way for the next story. For many, this reflects the experience of love: confusing, overwhelmingly powerful and yet often transient. “Done” is my favourite section and includes the stories “Somewhere Out There” and “Spring Uncoiled.” “Somewhere Out There” is a rumination on love and loss as a husband and wife visit the Alaskan wilderness that claimed their autistic son’s life to feel closer to him physically and emotionally. It is an interesting meditation on what connects us and the dangers of even the purest love. “Spring Uncoiled” is a surprising and compelling story which is no easy feat especially in that it is only five pages long and centres on one of the most well-known events from the Holocaust: Anne Frank’s life and capture. This story is a reminder that while spring is a time of rebirth, there must be death before that can occur. Never before has spring seemed so ominous and poetic. Babel via Negativa is published by the Singaporean press Ethos Books and won the Benjamin Franklin Book award and the second annual USA Regional Excellence Book Award 2016 in the Spirituality category for the Northeast region. The author Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé brings his academic training in theology to bear in this volume. The title Babel via Negativa references the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, and “via negative” refers to apophatic theology, or negative theology, which emphasises the unknowable nature of God and therefore focuses on describing God inversely. Spirituality and language are a central focus of this book, and the Tower of Babel reference is particularly apt in the elusive way that Kon uses words making language seem more divisive and deceptive than ever. The book which Kon calls “hybrid-scripting” operates as a kind of literary medley full of twisting forms being birthed and gasping in that instant where the pendulum swings between life or death. In short, it’s messy and it’s demanding. The book itself is very stylish featuring avant-garde architecture on the cover along with half of a picture frame while the back cover shows a carefully framed photo of ever receding doorways. Undoubtedly, this imagery operates as a kind of visual reminder that the contents rely heavily on framing devices. The guiding motif of the book is a set of wings which occurs no less than eight-six times and, with each occurrence, readers can feel Daedalus’ wings flapping perilously nearer to the sun. Playing with words is dangerous territory. The book is diced into five sections with the first three—”Tweet Goes the Poplar Tree,” “Poem In Media Res” and “Lost Acts of Translation”—focusing on language and the last two— “Roundtable On Negative Theology & Its Discontents” and “Five Dialogical Encounters”—focusing on religion. “Tweet Goes the Poplar Tree” is a collection of tweets that are in the literary genre of asingbol, which was invented by Kon. It consists of 140 characters (including spaces) which are to be read as literal, pure objects. I am not sure how this is different from any other tweet except that they are composed according to stricter typographical restrictions and are to be read in a particular way—as is this entire book. In the endnotes or stylised compass notes as they are framed in the text, we find another description of the book as “a babble of language at its most transcendental.” This is what the book aspires to, but it is a very difficult task, especially as it is not accomplished alone. Much is required of the reader, and it is always difficult to read difficult books. The reading experience is something like trying to meditate on transcendental poetry while listening to stream of consciousness scatting or being compelled to endlessly hammer round cylinders into triangular holes. It left me wondering why. If language is the enemy of any author, then it is also their lover whose arms they cannot escape. This brings me back to Chin’s “spoiled” love story in Nine Cuts, “The Writer’s Revenge.” An abused wife loves her abuser but also dreams about revealing his true nature to the community who reveres him. The story concludes with this: “It cannot be borne, what the heart tethers us to.” And yet, there she is bleeding in his arms, laying next to him, and here is another book about the enigmatic mistress that is language. Kon writes that “[as] with all writing, one can read into the enigmatic projections of an authorial self, one that alas remains elusive to the reader and indeed sometimes to the author. Such a liberal gaze, sometimes mistaken as intransigent, seems to me to rightfully restore the playfulness of reading as pleasure.” Such sentiments seem as one-sided as they are privileged. It is no wonder Kon references Daedalus and his wings throughout the text, for he too likes to fly close to the sun.   Stephanie Studzinski Stephanie Studzinski is a PhD student in Literary Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She is also a surrealist painter and carpenter whose works can be found at elucious.com. |