|

by Ng Yi-Sheng

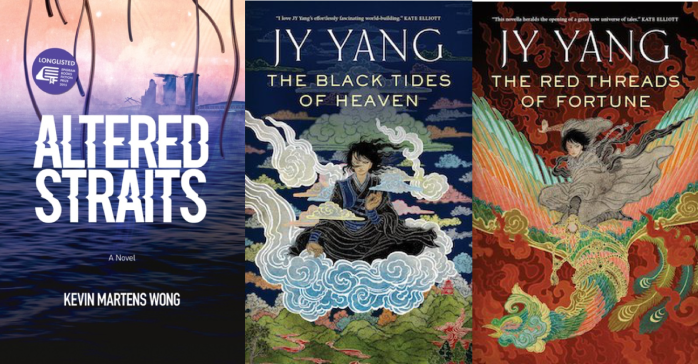

❀ Kevin Martens Wong, Altered Straits, Epigram Books, 2017. 384 pgs.

❀ JY Yang, The Black Tides of Heaven, Tor.com, 2017. 240 pgs.

❀ JY Yang, The Red Threads of Fortune, Tor.com, 2017. 213 pgs. Way back in 1993, sci-fi novelist William Gibson paid a visit to Singapore as a correspondent for Wired magazine. He summed up our over-regulated city-state with a pithy little moniker: “Disneyland with the death penalty.” Today, that metaphor still rings true, especially for us in the LGBT+ community. Things are pretty grim: gay sex is illegal, queer media is routinely censored and homophobic hate groups are incrementally pressuring authorities to remove any remaining representation we have left. Yet friends in neighbouring states like Malaysia and Indonesia actually envy us for our secular multi-racial government, our lack of state-sanctioned religious violence and our thriving gay nightlife. Disneyland with the death penalty. Pride with sodomy laws. We're not just a nation: we're a dystopia and utopia, all in one. Surprisingly, this atmosphere’s been pretty conducive to queer literature. Since the 1980s, Singaporean authors of all genders and orientations have drawn on LGBT+ experiences and oppression in their writing. In the past decade, we’ve also seen a renewed interest in speculative fiction, with folks using fantasy and sci-fi as means of grappling with our complex political and cultural identities. The two trends finally collided in 2017, yielding Singapore’s first queer science fiction novels: Kevin Martens Wong’s Altered Straits and JY Yang’s first two volumes of The Tensorate Series, The Black Tides of Heaven and The Red Threads of Fortune. These are extraordinary books, featuring polished prose and stunning feats of world-building. Wong’s was longlisted for the Epigram Books Prize, while Yang’s were published internationally by Tor.com, with one ending up as a finalist for the Hugo Awards. Coincidentally, both also feature a plethora of mythical and prehistoric beasts: merlions, nagas, garudas, raptors, kirin. What truly intrigues me, however, is how the authors each re-imagine Singapore in queer dystopian/utopian terms. First, let’s look at Altered Straits. The novel takes place in two eras, each set in a different alternate universe. In 1947, we visit the kingdom of Singapura, where native Malays have fought off British colonists by harnessing sentient merlions. It’s an almost absurdly utopian scenario, but brilliantly sketched: the militarised kingdom of Singapura now includes Johor and several Sumatran islands, there’s a war with the Sultanate of Sulu and the major world powers are the Russia and the Ottomans—other European nations were never able to establish empires in Asia and Africa. Our protagonist, sixteen-year-old Naufal Jazair, is conscripted into the armed forces as a merlionsman. He’s subjected to relentless trauma during training, inflicted by abusive fellow soldiers and the psychic process of bonding with the merlions. Though queerness is barely mentioned in this storyline—some soldiers have sex in the showers, which is frowned upon but not punished—it’s a resonant narrative for gay Singaporean men. Almost all of us had to do our National Service in Singapore’s military; many of us found it a toxic environment, in which our notions of manhood were constantly under attack. Meanwhile, in 2047, we encounter the underground fortress city of Singapore, one of the last bastions of humanity after the cyborg invasions of the Concordance. Our second protagonist, Titus Ang, is a young army officer tasked with the mission of travelling across dimensions. However, he harbours a deadly secret: he’s a gay man in love with another soldier, Akash, and in this society, homosexuality is punishable with grisly execution. In an early scene, a propaganda video plays on the MRT: gay men are fed live into meat grinders, turned into fodder for pigs and cattle. As horrific as this Singapore is, it’s also oddly utopian. It’s a society on the brink of apocalypse that’s somehow managed cultural diversity better than our own nation—an issue that Wong cares about deeply, as seen in his efforts to revive the endangered Eurasian language of Kristang. We’re told that there are six national languages here, including English, Malay, Cantonese, Tamil and Kristang. (We’re not told what the sixth language is, though we may guess it’s Mandarin.) In the MRT scene, polyglot station announcements play in the background as commuters watch the executions. Local religions and foods continue to thrive, and men and women of different races are equally represented in the military. Notably, both the Minister of Defence, Dr Zaid, and Titus’s comrade in arms, Salehah, are Malays—a significant choice on the part of the author, given our government’s policy of excluding Malays from sensitive positions. This world is thus a bizarre mélange of multicultural harmony and bigotry—incongruous, perhaps, but not unthinkable. After all, one of Singapore’s most prominent anti-LGBT movements involves an interreligious alliance between Christians and Muslims. What, then, of The Tensorate Series? Its tales are set in the Protectorate, a world of high fantasy—but with a few significant deviations from the norm. Cultural elements are borrowed not from medieval Europe, but from a multiethnic Asia. Characters—Mokoya, Akeha, Thennjay, Adi, Yongcheow, Wanbeng—have names derived from Japanese, Tamil, Malay and Hokkien. They eat stews of star anise and cardamom and practise religions resembling Buddhism and Islam. Western publishers call this “silkpunk,” i.e. an Asian version of steampunk. (I’d personally prefer spicepunk, acknowledging its Southeast Asian roots.) Just as crucially, this world has a completely different system of gender from our own. Children aren’t assigned a gender at birth; only when they approach puberty do they decide if they’re male or female—a major plot point in The Black Tides of Heaven, when the twins Mokoya and Akeha choose to be female and male respectively, effectively ending their years of childhood companionship. Similarly, homosexuality, bisexuality, nonbinary genders and polyamory are uncontroversial. Yang identifies as a “queer, nonbinary, postcolonial intersectional feminist,” preferring the pronouns “they/them.” It’s therefore tempting to believe they created the Protectorate as a utopia, where someone like themselves could live free from prejudice. Yet the world has dystopian elements aplenty. It’s led by the Protector, Lady Sanao Hekate, a dictatorial monarch who’s brutally suppressed rebellions. Like a former Prime Minister of ours, she views her subjects as digits—including her own children, Mokoya and Akeha, whom she exploits as children, first as barter, then for their psychic abilities. There’s an oppressed racial minority called the Gauris who struggle for labour rights. Yang isn’t content to create a paradise of sexual and gender liberation. Instead, they call attention to Singapore’s other injustices, demanding redress. Consequently, the core of the series is Mokoya and Akeha’s struggle to use their strengths to heal the land, and thereby heal themselves. Reading Altered Straits and The Tensorate Series, it’s easy to see the parallels between the two. Both fictions seek to represent, not only queerness, but also Singapore’s cultural diversity, as well as life under an authoritarianism. Over and over again, we see young people abused by dictatorial, parental figures: Naufal by his training officer Captain Nursayba, Titus by Dr Zaid, Mokoya and Akeha by the Protector, Princess Wanbeng by Chief Advisor Tan Khimyan. They find solace, not in the roles society forces onto them, but the relationships of love they forge themselves, whether it’s Titus and Akash’s furtive, tender romance, or the sibling alliance Mokoya and Akeha form as they reunite as adults. Ultimately, what thrills me the most about these two novels is their sheer originality. As Singaporeans, we often face doubts about whether we have a culture at all. We’ve been told by our own leaders that we can’t speak of ourselves as a nation: we’re too demographically fractured, with too brief a history, and far too small—and queer Singapore is smaller still. Nevertheless, Wong and Yang have proven that our tiny community can generate entire worlds, dazzling and disturbing, great and terrible. Be they utopias or dystopias, what matters most of all is that we have a place within them. These are our universes. Open them up. The story’s beginning.  Ng Yi-Sheng Ng Yi-Sheng is a Singaporean poet, playwright, fictionist, critic, journalist and activist. His books include last boy (winner of the Singapore Literature Prize 2008), SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, Eating Air, Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, A Book of Hims and Lion City. Additionally, he translated Wong Yoon Wah’s Chinese poetry collection The New Village and has co-edited national and regional anthologies such as GASPP: A Gay Anthology of Singaporean Poetry and Prose, Eastern Heathens, and Heat. He tweets and Instagrams at @yishkabob. (Photo credit: Joanne Goh) |