|

by Melissa De Silva

We are studying peribahasa, idioms. There are many lists to learn in Malay, seerti-seiras (synonyms), berlawan (opposites) and peribahasa. In primary school, my favourite Malay idiom was gajah berak besar, kancil pun mau berak besar. The elephant takes a big crap, so the mousedeer wants to take a big crap too. Seriously. It’s a cautionary statement about unrealistic aspirations. The other one I liked because of the absurd image: burung terbang pipiskan lada. To throw chilli at a bird in flight. The warning of not hurrying to take action until an event is certain. Some solid wisdom there. We are studying peribahasa, idioms. There are many lists to learn in Malay, seerti-seiras (synonyms), berlawan (opposites) and peribahasa. In primary school, my favourite Malay idiom was gajah berak besar, kancil pun mau berak besar. The elephant takes a big crap, so the mousedeer wants to take a big crap too. Seriously. It’s a cautionary statement about unrealistic aspirations. The other one I liked because of the absurd image: burung terbang pipiskan lada. To throw chilli at a bird in flight. The warning of not hurrying to take action until an event is certain. Some solid wisdom there.

Malay class at CHIJ Toa Payoh Primary was mostly made up of Eurasian girls who were terrible at Malay. A complete disinterest in the language might have had something to do with it. Out of the bunch of us, there were five actual Malay girls, a gravelly-voiced girl with cat’s eyes called Siti, tomboyish Azryn, another girl whose mother was a retired singer of 60s/70s fame, smiley Susie and tiny, perpetually scared-looking Kartini. One highlight was enforced singing on Fridays. I have no recollection of this, but my good friend Emilie Oehlers assures me of every detail in astounding clarity. Apparently we were forced to go up in pairs to sing songs in front of the entire class. In Malay. Emilie says she and Nicole Batchelor would always go up together and sing ‘Potong Bebek Angsa’ every Friday on repeat. Nicole recently sent me a link to the lyrics online and I managed to find an English translation. Now that I go over the lyrics as an adult, I realise the song is bizarrely macabre. It involves cutting up a goose, then for some reason, a dancing woman waltzes into the picture. It’s no wonder I blocked it out. These are some of the lyrics: Potong bebek angsa,

Masuk di kuali.

Nona minta dansa,

Dansa empat kali

Dorong ke kiri,

Dorong ke kanan,

Tralala lala lala lala la la This roughly translates to: Cut the goose’s breast

Put it in the wok.

The lady asks for a dance,

Dance four times

Push to the left,

Push to the right... Even now that I understand all the words, it still doesn’t make sense to me. What’s the relation between the woman and the goose? What’s with the pushing to the left and the right? Goodness knows what song I went up to sing. Clearly, I must have blocked out these happy events. Maybe I kept silent while my poor partner, whoever she was, did all the grunt work, or maybe I was sly enough to lip-synch. Back then as a child, I never understood why I was studying Malay. Why go through all this torture? This is not my mother tongue, thank you very much, I would tell my Cikgu silently in my head. My mother told me our mother tongue was English, but that didn’t seem right either. But more on that later. Now, in my thirties, I love the fact that I possess at least one Southeast Asian language, and shockingly, am at ease ordering nasi campur and kueh from a roadside warung in Malaysia. When I break out in my limited Malay vocab to taxi driver enciks across the Causeway, they look surprised when they hear I’m from Singapore. When I explain that I am Seani and I “belajar Melayu di sekolah,” that I am Eurasian and I studied Malay at school, they nod and go “Ah... bagus.” In their eyes is something like approval, and perhaps I’m crazy, but also something like pride. There is a Malay uncle assigned to clean my block, an adorable tiny man about five feet high. He has a face that reminds me of Popeye the sailor. The fact that he’s always in a faded olive cap adds to the sailorish quality, even though his headgear in no way resembles Popeye’s black and white skipper’s hat. The uncle also doesn’t smoke a pipe. Instead he has a wisp of a hand rolled cigarette dangling permanently from his mouth as he goes about sweeping the void decks and the drainage indents along our corridors. Still, the distinct Popeye-ness is there. Whenever I leave the house in the morning and see him in the vicinity, I make it a point to slow down or adjust my path so it takes me closer to him, so he can see me. Then he will look up and his whole face lights with a gummy smile. And I’ll try to get in a “Selamat pagi,” before he does. Yes, I feel ridiculously pleased that I can do this. Once I even chanced upon him at the bus stop near my block, after he had finished work. And I did something I later laughed at myself for, for my sheer mad ambition. I went and sat next to him on the cement bench and tried to have a conversation with him. In Malay. Well, he spoke Malay and I kind of understood eighty percent of what he said. Mega achievement. I didn’t speak very much back though. He told me he’s assigned to a few blocks, what time he starts work each morning and that he ends at 3pm each day. Also that he has Sundays off. I don’t know what he thinks I ‘ am’, orang Serani or just someone who happens to be able to speak really bad Malay, but it doesn’t matter. Just being able to have that exchange at the bus stop as the six lanes of traffic roared by, was a testament to human affinity with this man who until then had hovered at the edge of my existence each day (except Sundays). All made possible by those Malay classes taken so very long ago. But when I was a child, I hated the mandatory lessons that seemed to have nothing to do with me. The first week of primary school, I confronted my mother. The conversation between my seven-year-old self and my exasperated mother went something like this: “Mummy, what’s our mother tongue?” “English.” “Then why am I taking Malay in school?” “Because it’s easier than Tamil or Chinese.” “Why would I be taking Tamil or Chinese?” “It’s just easier. You want to learn Chinese or Tamil characters, is it?” “No, but we are not Malay what. Why do I have to take Malay if I’m already studying English?” “It’s just the rules of school.” “They said in secondary school we can choose Spanish or French or German.” “So?” “Can I take Spanish?” Later, I was to discover that Malay would be one of my threads of cultural inheritance, not by any specific ancestor I could trace and name, but through reasonable assumption. Since the Portuguese colonised Malacca and intermarried with local women, some of them would certainly have been Malay. I believe it’s safe to assume that I have at least some Malay heritage. So those Malay lessons were not irrelevant to my existence after all. In time, I came to see them as an enriching opportunity to experience another language and culture I would otherwise never have had access to. Fast forward to 2016. I have been attending mother tongue lessons of a very different sort. These are of my own volition, and conducted by a teacher much younger than myself. The most significant point though, is that for the first time in my life, I am formally learning my mother tongue. Which is not English. Of course, Kristang, being a creole of Portuguese and Malay, isn’t every Singaporean Eurasian’s mother tongue. Eurasians of other threads of heritage may count many other languages — German, Khmer, Thai, French, for example — among their wealth of mother tongue inheritance. But since my four grandparents all were of Portuguese-Eurasian heritage (my maternal grandmother’s maiden name was Sequeira, my maternal grandfather was a Pinto, my paternal grandfather a De Silva, and my paternal grandmother’s family name was Pereira), for me Kristang is truly my mother tongue. The course is conducted by linguistic student Kevin Martens Wong, whose mother is Eurasian. The linguistic wonder basically learned Kristang on his own by reading up and memorising the scant available material, such as a handful of dictionaries and a few books and poetry collections written by a Kristang activist in Malaysia by the name of Joan Marbeck. There is no socialist regime enforced public singing. Instead, we play games, which are pleasantly trauma-free. One lessons, we played a game called Mar di Rikeza (Sea of Riches). This sprang from the brain of Martens Wong. The objective was to get us used to the names of the cardinal points and colours. A map of the Bijagos Archipelago, off the coast of Guinea-Bissau (another former Portuguese colony in the West Africa) was projected on the wall. The Bijagos Archipelago is a modern day smugglers’ hideout, complete with drug cartels. Really. So naturally, our goal was to look for treasure. Each of us was represented by a ship on the map. We would have to call out in Kristang where we wanted our ships to move — north-northeast, for example. If your ship happened to pass over a coordinate where treasure was hidden, it was yours. The treasures were romantic and colourful — the Spada di Floris (Sword of Flowers), Korsang Jambu (Ping Heart), the Diamanti Azul (Blue Diamond). But the life of a mariner is never plain sailing. We also had ‘pirates’ on our tails, other students and our other teacher Mr Bernard Mesenas, an elderly gentleman. They had to power to snuff out our lives. Exciting times. For the First time since primary school, I have made a group of Eurasian friends — mother and daughter Mary and Eleanor Thomas, Kevin Michael Sim and Sharlene Pereira. And I mean friends, not just classmates. We hang out together after the Saturday morning lessons at NUS, and we’ve gone to the same restaurant for lunch in Holland Village so many times after class that we’ve been rewarded with a free round of chocolately desserts by the wait staff. My friends’ reasons for learning Kristang overlap with mine. Kevin Michael Sim thinks of it as “his grandmother’s tongue” and Eleanor wants to speak it to her own family one day. It makes Mary feel more connected to her ancestors. Being able to speak in simple Kristant with them makes me feel more Eurasian. And I am beginning to feel like I have more of my own culture, which I’ve never felt like I had very much of, since I was a child. We Eurasians do not have many visible, tangible traits to point at and go “Ta da! Culture!” We cannot boast of having unique beaded slippers, say, like the Peranakans, or a legacy of dynastic culture like the Chinese, or a wealth of literature, art and song like those from the Indian subcontinent. But what we do have, besides our awesome Eurasian cuisine, is this language, which is truly ours. A few lessons into the Kristang course, I came across a quote by Nelson Mandela: “When you speak to a man in a language he understands, he understands you with his head. When you speak to him in his mother tongue, he understands you with his heart.” A few months earlier, I wouldn’t have understood what he meant, not truly. But after tasting my own language, I do. Now I am beginning to understand that a mother tongue is the language that speaks to the deepest of a person’s heart. It is the framework that shapes our worldview and articulates our physical, emotional and spiritual being. Possessing a tiny bit of Kristang — a treasure that grows with each lesson — gives me a feeling of stepping into a new world, a world that belonged to me all along, but now, finally, I have the key. Editors' note:

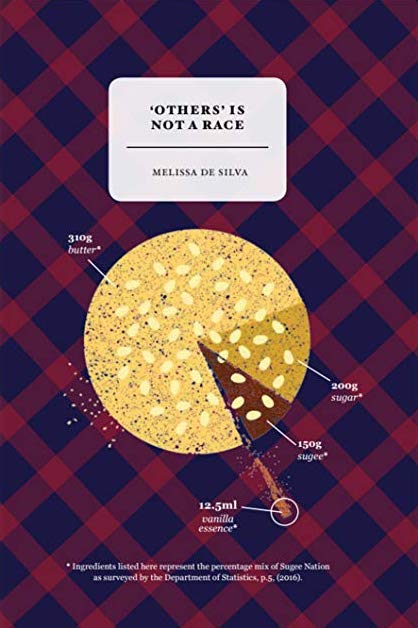

"Mother Tongue" is included in Melissa De Silva's "Other" is Not a Race (Math Paper Press),

a winner of Singapore Literature Prize 2018.  Melissa De Silva Melissa De Silva is the author of ‘Others’ is Not a Race, awarded the Singapore Literature Prize 2018 in the Creative Non-fiction category. Her fiction has been published in Best New Singaporean Short Stories Vol. 3, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore and LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction. She has just finished writing a historical novel set in Singapore during the British colonial era. De Silva is Singapore's Education Ambassador for online global creative writing platform Write the World, which promotes writing across genres among teens. She has worked as a magazine journalist and book editor. |