|

by Mohamed Latiff Mohamed, translated from Malay by Nazry Bahrawi

“Slog. Slog, fools. Stupid… cattle. So stubborn! Slog siuuhhh! Huhh,” shouts the Master as he whips the bovine pair in turn. The animals pant and writhe as they toil, their cheeks perpetually wet with tears. On sporadic occasions, they excrete greenish goo along the road that they trudge. Goo that sticks to the wheels of buses and cars. Goo that will eventually envelop hundreds of kilometres of asphalt along this road. “Slog. Slog, fools. Stupid… cattle. So stubborn! Slog siuuhhh! Huhh,” shouts the Master as he whips the bovine pair in turn. The animals pant and writhe as they toil, their cheeks perpetually wet with tears. On sporadic occasions, they excrete greenish goo along the road that they trudge. Goo that sticks to the wheels of buses and cars. Goo that will eventually envelop hundreds of kilometres of asphalt along this road.

Last night, the pair plotted to defecate to the best of their ability. Let cattle goo stain human roads. A productive day performing this misdeed has always accorded them a sense of vengeful satisfaction. In fact, last night also saw them conspiring a suicide pact, to fall dead smack in the middle of the busy human road, to stop traffic with their unmovable carcasses. However, when the ropes encircling their muzzles are yanked and jerked, they are left with little choice but to abide by their Master’s orders. While it looks harmless, the black nylon rope that links human to cattle stings their nerves, cutting the cartilage of their noses when wrenched. Each pull feels like an electric shock meant to dictate their actions. The beatings are nothing compared to the rope-yanking. The pain of each pull resonates in the very kernel of their being. “I am at my wit’s end as to how else we can rebel against our Master. We have attempted everything. Yet we are still tormented. We drudge all day but are fed rough, dry thatch. I can no longer take this. I must act tomorrow. Must act,” says the enraged bull to the female. The night is chilly. They are tied to a jackfruit tree, barren of leaves. They can feel the cold in their bones as the dew seeps through their hide. “Forget it. Let us persevere. This is our fate. We are cattle. Once a cow, always a cow. We are beasts in the eyes of these humans. With our muzzles pierced, our freedom shackled, how are we to rebel?” says the female as she attempts to calm her partner. “This is what I despise. Conceding. Always conceding to ‘fate’. God too despises us if we are always conceding defeat when we were made to be noble. My father lives in the land of Pancasona where cows are hailed as sacred. I know that humanity there see us as noble creatures. All this proves that we are ignorant here, to the extent that we have allowed them to enslave us, to pierce our snouts, an act that we can blame no one but ourselves. We have our dignity, and God is fair. There, our meat is off-limits for the humans; it is in fact sinful for them to consume it. We are noble, we are sacred, and humans worship us. Are you even aware of this?” The bull belched, defending his honour. The female blinks as he goes on with his tirade. She comes closer to him, as if searching for the warmth emanating from his rage. The male stares defiantly into the night as the pale moon recedes into the comfort of the clouds. “That is in Pancasona. But we are not in Pancasona. The saying goes: ‘Wherever in this earth we trudge, there too must we uphold the skies’. You just heard imaginary tales from your father. Surely the humans do not honour cows. Impossible. I do not believe you. If that were true, how could our fate be this bad here? A fate far worse than excrement. At least excrement can be recycled as fertilisers. Here, our fate is worse than a carcass riddled with maggots.” “Our experience here could not be more different than our kind in Pancasona. Surely our standing with the humans here could not be drastically different. I am unconvinced. These are just imaginary tales from your father.” Having expressed her scepticism at the bull’s assertions, the female sits herself in a coiled position. Under the cover of the night, their bodies collectively resemble a pitch-black knoll. The bull also lays his body close to hers. His breaths, full with the smell of grass and lalang, slap her cheeks. “You are foolish. You do not know the world. Your world is this place, your world is under this jackfruit tree, this listless, leafless tree. Fine if you do not believe me but that was what my father told me. He was not a daydreamer. He was tough and fierce. A bull of few words. He was the only bull to mull over his bad luck in this place. He was constantly thinking of a way to elevate our standing such as escaping back to his birthplace. To me, my father was an imaginative philosopher,” counters the male. “My father said that pictures of cows are displayed in gold frames, their necks collared with flowers. Sweet, fragrant flowers. Dowries are made for us. We are the bride and groom. Newlyweds worship us. They want us to bless their marriage. According to my father, no cows need to work there. All day, they just sit, eat and sleep. They hang an adorable bell around our necks that chimes with our every movement. Oh! What a charming life we could lead in Pancasona. How joyous. How idyllic.” The bull continues recounting his father’s tales, told to him about two decades ago. He was a calf then. His father would regale him with these stories as he suckled his mother’s milk. He has never forgotten them. In fact, they serve as inspiration, giving him the moral fortitude to continue living, fuelling his desire to escape. He will make his way to heavenly Pancasona. His father’s tales have become his source of strength from which to face the bitter, dark world. “My father wished to see me continue his struggle. He had invested a momentous amount of hope in me. He left me with these words, that he will continue cursing me, that his soul will chastise me if I allow myself to be enslaved by the humans. “My father had also warned that I should never give in to fate. I must never let my muzzle get pierced by the humans. He said that once that happens, it would spell the end of my potency. ‘You would do anything the humans tell you. You would eat a pig’s droppings, rape your own mother, insult your own brethren, if they instructed you so. You would do the most despicable things once they slap a nose ring on you. I will never call you my son if you keep silent and refuse to act once I am gone, if you do not resist. You must be bold even when your life is at stake. What kind of life do we lead? It is better to die for the cause of revolution’. These were my father’s words. “Struggle for truth and fight against oppression. God scorns those who just submit themselves to the whims of fate, those who surrender themselves to what destiny has in store for them. Indeed, God loves those who strive for their rights. I can still recall my father’s advice!” As the bull carries on his lengthy diatribe, the female keeps silent. A faint rooster’s crow can be heard in the distance. The barking of dogs disturbs the stillness of this dark night. “I must act tomorrow. I will run amok. I will plough through our owner’s stomach till his entrails lay bare. I will intimidate the entire village. Whoever tries to stop me, I will break their bones. I will stab my horns through their eyes, and right at their groins. I will do these tomorrow. Even if they were to hack me to death with their sharp knives, even if they were to make mincemeat out of me. Even if my head were to get bashed in by their metal trowels. Even if… even if. All that live must one day die. Soon the tale of my rebellion will spread among generations of cows to come. And our brethren in Pancasona will hear of our plight against the humans. And they will come in hordes. They will pray, supplicate, beseech, curse and disparage the humans. And God will punish the humans with an apocalyptic flood and earth-shattering earthquakes. Tomorrow, indeed! Tomorrow I will surely act.” As before, the female blinkingly gazes at the bull. She has never seen him quite so riled up. He has clearly run out of patience. She holds the gaze, the sparkle in her eyes matching the sparkle of her partner’s. The wind begins to pick up, ushering in the chills as the listless, leafless jackfruit tree stands obstinately still. The night is nearing its twilight. “You must not forget our child in my womb. If you are killed, then what will happen to me? Have pity on our unborn calf, have pity on me. If you wish to act, do it after our child is born. This is our first child. Would you not want to see its face? It will surely bear your looks. Do you not want to kiss it? Do you not wish to play with it? Be patient. Be patient till our child is born. Have pity on our sinless calf. Please be reasonable and not rush into this,” pleads the female. The sadness in her voice gives the bull some pause. He peers into the night. By now, the moon has completely taken refuge behind a bevy of thick clouds. The sound of roosters crowing begins to dominate the landscape. “It is unfortunate that we were not sterilised. It would have been better if we were childless. It is not that I do not love our progeny. There is no father who does not care about his child. But I regret this inevitable birth. It is better if our child dies, for I feel guilty bringing it into this world. All I am doing is creating yet another slave for the humans, allowing one more cow to have his muzzle pierced. I am only prolonging our enslavement. I have committed a cruel act. If we live in Pancasona, I would gladly father dozens. But we live in this godforsaken place.” He sighs as his gaze returns to the night. The female is rendered silent by his admission, touched by his love for the child in her. “I figure we have been caged by fear. The fear represented by the rope attached to our nose rings. For centuries, people have said that once a nose ring is placed on a cow, that creature is easily enslaved. But let us try to change our attitudes, the way we think. Let us imagine that this nose ring is not there. Surely we will stop feeling the pain, and we can ignore instructions. Right there is our weakness,” exclaims the bull. He appears to have reached an epiphany about avoiding the pain caused by his nose-ring. He rises suddenly, urging his partner to do the same. He stands straight on all fours as the female looks at him confusingly. “Bite. Bite the rope that binds us.” The female did as she was instructed, biting with an outburst of gargantuan energy. Bite after bite. Fast and furious bites. Recurrent bites. Incessant bites. The rope suddenly snaps. “Why wait till tomorrow? We run now. Come. Follow me.” The bull runs swiftly, his partner closely trailing him. They brave through bushes. They ram through the night. They ram through the dew that is fast enveloping the earth. They continue to run even as they start panting. They run towards heavenly Pancasona. Some two hours later, they reach the edge of a pond. There, the bull encounters a herd of his brethren cows. They happen to be drinking from the pond. Their muzzles are not pierced. They look free, fattened and fresh. He approaches them. He starts to pontificate. The other cows listen to him attentively. At the end of his speech, they start running and shouting, “Pancasona! Pancasona! Pancasona!”. They chance upon other herds whose members decide to join their march to freedom. The cows now number in the thousands. More are coming. They run till dust-cloud forms beneath their thundering hooves. The dust-cloud reaches the clouds. Still, the stampede continues. They now occupy the roads as cars are stopped dead in their tracks. The humans begin to flee from them as the cows run through those who fall. Many humans perish under their hooves. Some have their skulls smashed, others have their entrails pierced. Cars are overturned. The cows have taken over the roads, wail the humans. Pancasonaaaaaa! Pancasonaaaaaa! Pancasonaaaaaa! Dozens of red and green trucks now surround the cows. A hail of bullets rain upon them. Many fall dead. Yet they continue on as thousands of bullets are expended. More cows fall. But those who survive continue their charge. This lasts till the humans manage to break their assault. Littering the road are thousands of cattle casualties. But a few manage to escape the brutal backlash. They run like the wind, and in their minds, a singular aim—heavenly Pancasona! Editors' note:

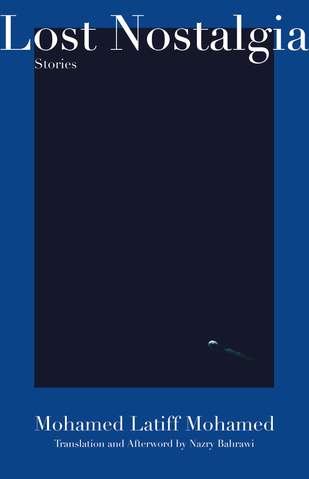

"Bovine" is an excerpt from Mohamed Latiff Mohamed's Lost Nostalgia (Ethos Books),

translated from Malay by Nazry Bahrawi.  Mohamed Latiff Mohamed Mohamed Latiff Mohamed is one of the most prolific writers to come after the first generation of writers in the Singapore Malay literary scene. His accolades include the Montblanc-NUS Centre for the Arts Literary Award (1998), the SEA Write award (2002), the Tun Seri Lanang Award, Malay Language Council Singapore, Ministry of Communication, Information and Arts (2003), the National Arts Council Special Recognition Award (2009), the Cultural Medallion (2013), and the Singapore Literature Prize in 2004, 2006 and 2008. His works revolve around the life and struggles of the Malay community in post-independence Singapore, and have been translated into Chinese, English, German and Korean. Two of his novels have been translated into English as Confrontation (2013) and The Widower (2015).  Nazry Bahrawi Nazry Bahrawi is literary critic and educator at the Singapore University of Technology and Design. As a literary translator, he works on transforming Bahasa texts into English. He has translated Nadiputra’s play Muzika Lorong Buang Kok (2012), Fuzaina Jumaidi’s poem "Tika Hamba Menjadi Tuannya" (2015) for the Mentor Access Project that is managed by the National Arts Council of Singapore, as well as the 2017 winning short story for the Golden Point Award, “Balada Kasih Romi Dan Junid”. He has also subtitled the classic Malay film Noor Islam (1960) produced by Cathay Keris. Bahrawi was formerly the interview editor of Asymptote, an international journal of literary translation. |