by Denis Mair

My friend Meng Lang passed away in Hong Kong on 12 December 2018. The fact that I heard the news on my birthday (16 December) is perhaps an indication of our close karmic tie. His death is a jolt of mortality for me, because he was ten years my junior.

You can read a New York Times obituary about him here.

Meng Lang was active in the underground poetry scene from the mid-1980s. He was co-editor of an anthology of underground and non-official poetry published in 1986: An Exhibition of New Poetry Groups《86年诗群大展》. He left China in 1995 to spend three years as visiting poet at Brown University. After that he remained in exile, dividing his time between Boston and Hong Kong. Meng Lang’s passport was revoked when he left mainland China in 1995, so he was unable to go back to visit his family in Shanghai. He was given special “white travel passes” to return to Shanghai three times, for very short periods, to visit his ailing parents and attend their funerals.

Early in the new millennium he married Du Jiaqi, a Taiwanese lady who taught literature at Lingnan University in Hong Kong. For the first few years of his marriage, he could only visit Du for short periods, until his application for Hong Kong residency was approved (perhaps because the Hong Kong government was wary of paper marriages). So he lived like a migratory bird: each year he made two big migrations between Boston and Asia; then, during his times in Asia, he made small migrations between Hong Kong and Macau or Taiwan.

After his wife retired from teaching in Hong Kong, he lived with her in Taiwan, but when his illness became serious, he returned to Hong Kong to seek medical help. He was a rare bird in many ways—a mainland Chinese dissident poet who held residency in Taiwan. Newspapers in Taiwan and Hong Kong often interviewed him or asked him to write about dissident issues.

I would like to share some of my memories of my poet-friend.

Every year as June 4th approached, Meng Lang was always involved in planning for the June 4th Tiananmen memorial observances, wherever he happened to be. At Harvard a candlelight vigil was held every year with readings and speeches on the Green. Some years when Meng Lang was in Hong Kong he helped to plan very big memorial gatherings.

In 1999 I hosted him when he came to Los Angeles. I drove him around as he took care of preparations for memorial activities. We arranged a reading and slideshow at Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center; we also set up a table on the Santa Monica Promenade. There was a candlelight vigil at the Chinese Consulate, organised by a group of L.A. artists.

Someone asked Meng Lang if he would keep on organising memorial activities every year and why. He said, yes, he would, because it’s just as important every year. And he did keep it up until he got deathly sick.

Meng Lang was a smoker in his twenties. In his forties he quit tobacco for good. He also fought off two bouts of tuberculosis, once as a young man and once during his exile in Boston. Although his illness was controlled by anti-tubercular drugs, I believe it left his lungs susceptible to cancer.

Meng Lang’s good friend Yan Li told me three months ago that Meng had been hospitalised in Hong Kong with terminal cancer. To this sombre news, Yan Li added a personal remark: “Meng Lang and his wife had bought a house in Hualian (a culturally rich town in Taiwan). After many hectic years, they were planning to settle down and enjoy life, and that’s when he was stricken by this fatal illness.”

During Meng Lang’s years in Hong Kong, he published several books about institutions, societal conditions, and possibilities of change in China. He published them under the imprint of two small presses: Morning Bell Press and Waves Culture Media. These books were written by mainland scholars and thinkers, but due to government censorship they couldn’t be published in China. They were niche-market books, sold in small bookstores in Hong Kong. They were published with grant money. Meng Lang had to jump through lots of bureaucratic hoops to apply for publishing grants.

He also edited an anthology of June 4th memorial poems, and an anthology of poems dedicated to Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo.

He had many friends from mainland China who got together with him whenever they passed through Hong Kong; they took each other out to dinner. So he was very well informed for someone who wasn’t in the government.

All these details are just the outer lineaments of Meng Lang’s life, but his true story—his true biography—lies in the trajectory of his poems. He was a poet who found his own unique path to write about the social, political realities of his country in the language of modern, avant-garde thought. As a poet he always faced political realities, never going down a rabbit hole of metaphysics or aestheticism, yet each poem demonstrates his powerful artistic sensibility. I reaped tremendous reward by translating over a hundred of his poems, and I am proud that he trusted me with his beautiful creations.

You can read my translation of seventeen poems by Meng Lang in the June/July 2019 issue of Cha. There are also a few poems by him on my PoemHunter page:

***

A few memory-snapshots of Meng Lang:

1) We were setting up a table with information about Tiananmen on the Santa Monica Promenade (I think in 1999). The artist Hei Feng had sculpted a six-foot Goddess of Liberty in dense grey polystyrene. (He made her a bit sexier than the goddess of liberty in New York Harbour.) I remember Meng Lang hoisting the statue from the bed of a pickup truck and setting it up behind the table on the promenade. He carried that faux-stone sculpture with theatrical flair, emphasising its unexpected lightness, but at the same time acknowledging its heaviness as a symbol.

2) During that same LA visit, Meng Lang and I drove down to Anaheim to see Li Bing, a poetry-loving businessman who happened to be in LA for a convention. He was staying in a roomy suite at the Anaheim Hilton, and he invited us down for a visit. We took sleeping bags and carried them across the luxurious lobby. Meng Lang looked perfect carrying a sleeping bag to camp out in his friend’s room, as if that were the most natural arrangement in the world. I spent an enjoyable evening camping out on the floor and listening to Li Bing and Meng Lang catch up about their mutual friends in the underground Shanghai poetry scene.

3) Much earlier, when Meng Lang was visiting poet at Brown University, a choreographer/dancer from China was invited to an arts festival at Brown University. Upon arrival, she became friends with Meng Lang and confided in him that she was pregnant; she did not wish to return to China, and she intended to apply for an H-4 visa to remain in the U.S. as a person of special ability. Meng Lang stepped in as surrogate father for her child and even went to parenting classes with her. As her housemate, he was there for her, to help during the first months of her baby’s life.

4) When I visited Meng Lang in Boston in the late Nineties, he was working as receptionist at the China Culture Center (an organisation located in the Boston theatre district, founded by Doris Chu, who was Meng’s benefactor in Boston). During his work at the Culture Center, Meng Lang helped plan exhibitions and programmes. He also was the convener of an informal group of émigré artists and Chinese overseas students who gathered to watch films or eat hot pot. Sometimes the gatherings turned into dances. On one occasion a participant who had indulged in too much liquor began kicking the wall and shouting. I saw Meng Lang wrap his arms around her shoulders and speak soothingly until her fit passed. I knew his embrace was pure-hearted, because as planner of those gatherings, he wanted to give people chances to communicate frankly. His role was secular, as a social facilitator, but his identity as poet was part of everything he did, so I felt that his role there was also in a sense spiritual.

5) I was house-sitting for an Evergreen College professor in a forest house near at Oyster Bay (Hammersly Inlet) in South Puget Sound. The rhythm of my life slowed way down, so I had time to read and absorb a few classical texts. Around that time Meng Lang was staying for a few months in Seattle. He and Yan Li drove down to Shelton, WA to visit me. We hiked down to the inlet at low tide and stumbled upon a lucky find – high winds and rolling waves had blown numerous large, live oysters up past the low-tide line. We didn’t have a bag with us, so Meng Lang took off his shirt and used it to bundle up the oysters we gathered. An oyster patrol plane flew overhead and waggled its wings at us. We climbed a trail off the beach and carried our load of oysters back to Nancy Allen’s house. Our exertions had sharpened our appetites, and Meng Lang was always partial to shellfish. We made a big delicious pot of oyster stew. One of the best meals of my life. The three of us talked late into the night.

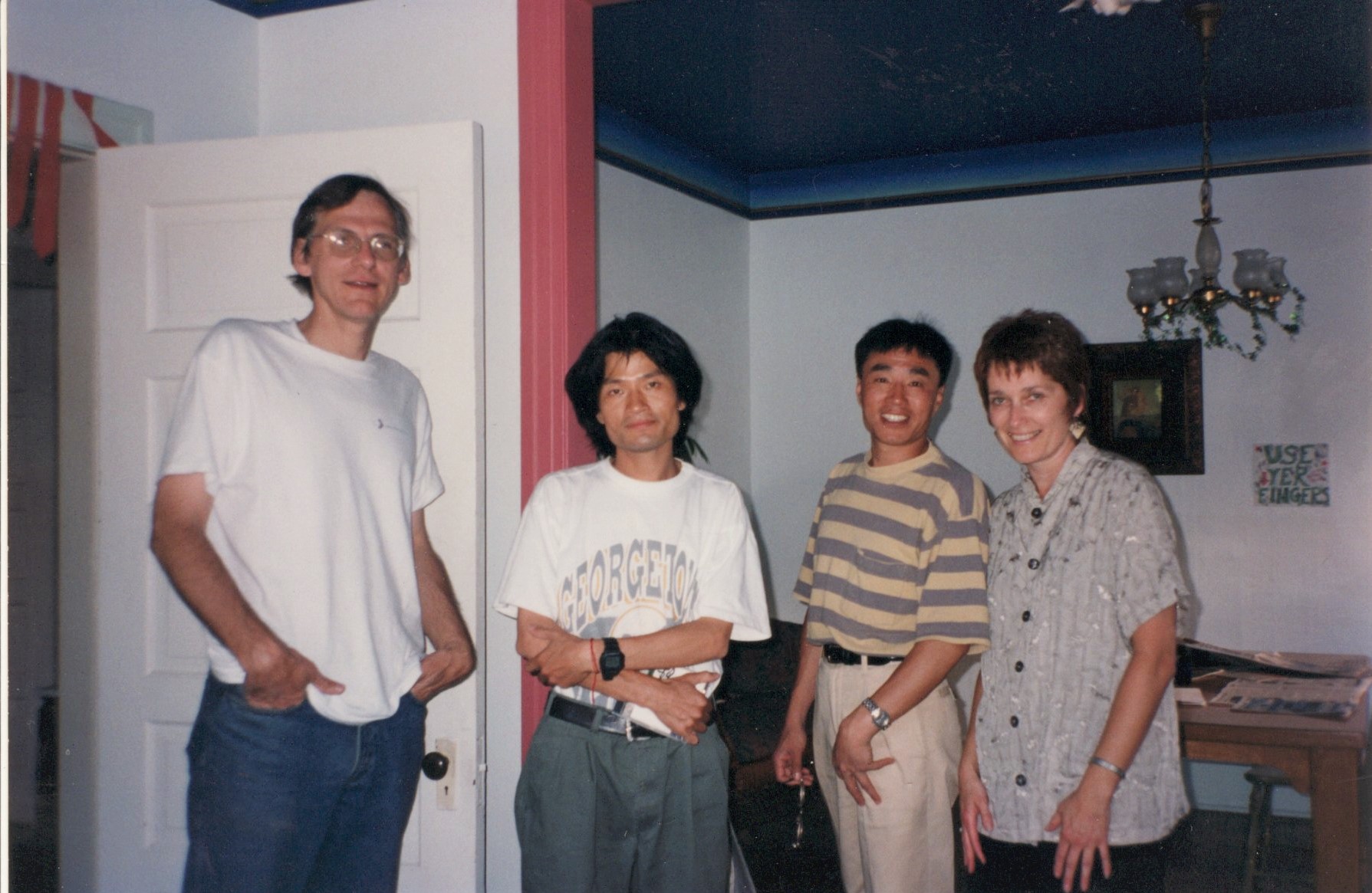

The pictures below were taken by my sister Heidi Mair. They were taken in 1993, when Meng Lang and Yan Li came to Seattle to take part in Bumbershoot Festival.

![]()

Denis Mair holds an MA in Chinese from Ohio State University. He was a research fellow at Hanching Academy in Taiwan and is currently translator for Jidi Majia, Secretary of the Chinese Writers Association. He has translated books by the monk Shih Chen-hua, the philosopher Feng Youlan, and the art critic Zhu Zhu. His poetry translations include: Jidi Majia, Rhapsody in Black: Poems (Oklahoma); Jidi Majia, Shade of Our Mountain Range (Mkhiva Foundation); Luo Ying, Memories of the Cultural Revolution (Oklahoma); Jidi Majia, From the Snow Leopard to Mayakovsky (Kallatumba Press); and Yang Ke, Two Halves of the World Apple (Oklahoma).