by Paoi Wilmer

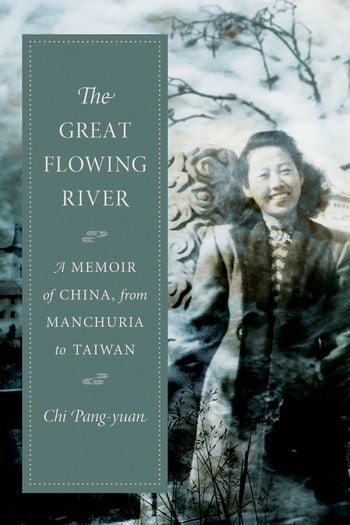

Chi Pang-yuan (author), John Balcom (translator), The Great Flowing River: A Memoir of China, from Manchuria to Taiwan, Columbia University Press, 2018. 480 pgs.

Born in China in 1924, Chi Pang-yuan is the daughter of Chi Shi-ying (1899–1987), a prominent military and political leader of the anti-Japanese resistance in Manchuria who was, for a period of time, a high ranking officer in Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party. Chi likens herself to her father as an idealist and an educator; they both tried to follow their heart in polarised political environments and believed in education as the foundation for building intellectual and moral excellence. Throughout her life, Chi strove for self-improvement and dedicated time to promoting educational and literary development in Taiwan. She taught at National Taiwan University; established the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at National Taiwan Chung-Hsing University; was awarded two Fulbright fellowships to teach and study in the United States and was a guest professor in Hong Kong and Berlin later in life. During her time at the National Institute of Compilation and Translation, she edited and translated contemporary works of Chinese literature for an international audience and oversaw the compilation of new Chinese textbooks for school children in Taiwan. She is proud of her contributions to Columbia University’s Modern Chinese Literature from Taiwan series with publications such as An Anthology of Contemporary Chinese Literature (1975) and The Last of the Whampoa Breed (2004). In addition to all the above, she was also chief-editor of Chinese PEN, an international literary platform for writers in Taiwan.

The Great Flowing River is a compelling account of life in a war zone, the perils of mass migrations and all the artifices of revolution. Chi uses many real and metaphorical rivers to convey the confluence of events and the passing of time. Her father fought with General Guo Song-ling’s army until they were defeated by the Liao River which they would never cross. Wuhan University, where the Qing-yi River met with the Da-du River to flow into the Min River, was a place where Chi came of age and found her calling: “my soul, this mind of mine urgently pursuing admirable knowledge, seeking beauty and goodness. In that little paradise on the riverbank I could concentrate on collecting my soul.” For Chi, rivers provided nourishment, consolation, strength and guidance at every stage of her life. Though she sometimes felt like a leaf adrift on the tides of history, when human tears formed rivers in the years of war and hardship, she took comfort in the knowledge that each and every life flowed into the great ocean of humanity. The allusion that rivers converge and also diverge, some flow gently and others too rapidly to cross, that they can cleanse as well as curse is a beautiful metaphor of life.

David Der-wei Wang points out in the introduction that Chi herself failed to cross the Great River of her academic dreams just like her father failed to capture the final city. In her usual fashion, she doesn’t point fingers but only implies that motherhood and wifely duties prevented her from achieving a Master’s degree when it was a mere few months away from completion. Yet of all the Great Rivers that are mentioned, it is the one she assiduously avoids that I find most interesting. There are a few possible explanations for her refusal to engage in politics. Firstly, she disliked and preferred to ignore the politicised environment in China between the Nationalists and Communists. Secondly, she followed a Westernised literary trend that espoused bourgeois ideals of art for art’s sake. Thirdly, after she settled in Taiwan, she may have wanted to remain neutral and non-committal in an unfair system where she could easily have been regarded as a perpetrator. Of these three, I find the last one most elusive and problematic.

In Wang’s view, if readers cannot comprehend the complicated sentiments that Chi feels for Taiwan, then they will not be able to appreciate what she’s trying to say in her book. For sure, Chi herself asks several times: do I love Taiwan? The answer is meant to be a rhetorical one, but it really is not as straightforward as we are expected to believe. Although silence is a useful tool, it is open to insincerity. In 1947, not long after the February 28 Incident, Chi left her troubled motherland and followed the Nationalist Party to Taiwan. Although this is a defining juncture in her life and the incident was no minor event for her adoptive country, it receives no elaboration and is immediately relegated to the footnotes. If one is unaware of this silencing, then it would be easy to interpret her apathy towards the Japanese people whose jobs and houses she and her newly arrived countrymen were appropriating. Her own job at National Taiwan University, originally called Taihoku Imperial University, was the result of a vacuum created by the repatriation of Japanese professors. But this begs the question: why were there no local leaders or intellectuals to appoint to the Legislative Yuan, university posts and corporate management roles? Weren’t the Taiwanese also Chinese, now that the Japanese had been sent home? Chi writes: “The situation in Taiwan gradually stabilised in the 1950s, and the government in its early stages was able to improve life on the island.” Gradually stabilised and improved in what sense and for whom? When viewed from a different perspective, specifically one taken from A Taste of Freedom: Memoirs of a Formosan Independence Leader by Peng Ming-min (1923-present), who Chi singles out as an ingrate, Chiang Kai-shek and his people brought “an era of gross exploitation” and his troops “effectively destroyed a generation of Formosan [Taiwanese] leaders and began the systematic destruction of an emerging conservative Formosan middle class.”[i] Under these circumstances, the February 28 Incident cannot be treated lightly and dismissed as a blip in history, especially when Chi’s own memoir is a direct appeal to our compassion for her brutal experiences under the different regimes in her own “motherland.”

If one can escape these complex undertows of history and politics, then the experience of reading The Great Flowing River is a congenial one. The translation faithfully conveys the moving story of an individual swept up by epic historical events. We celebrate with Chi as she develops from a “weak,” “bookish,” “muddle-headed” girl living like a refugee in her own country into a resilient and strong woman successfully established on a new land. It is her love for literature and her belief in its value to mankind that gives her hope and the strength to build meaningful relationships with those around her. On the surface, it is a wonderful account of a committed scholar and her joyful love affair with literature. Yet I cannot help but wonder what we will find if we dive deeper into her silences.

[i] Peng Ming-Min, A Taste of Freedom: Memoirs of a Formosan Independence Leader (New York: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, 1972) x, xii.

![]()

Paoi Wilmer is a part-time teacher at Durham University’s School of Modern Languages and Cultures (2014-present) who received a PhD from Royal Holloway, University of London. She lectured in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at National Taiwan University from 2003-2010. She served as Deputy Editor of National Taiwan University Press’s East-West Cultural Encounters series and she serves on the advisory board of the journal Encounters. Her articles and reviews have appeared in many international journals from Israel, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Hong Kong. She loves to paint in her free time and has exhibited artwork at various exhibitions in the North East of England.