by Jennifer Mackenzie

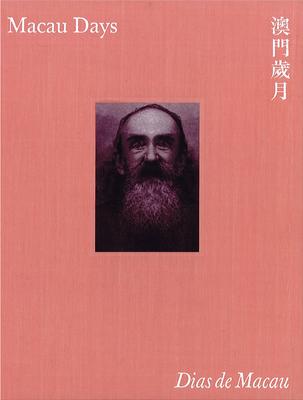

Brian Castro & John Young, Macau Days, Art+Australia Publishing, 2017. 187 pgs.

For more than five centuries, the days spent in Macau have inspired and nourished those on the bird’s path, the flight out, those who have given their lives to the great transformation. This exhibition is for those people, and those days spent, in Macau.

—John Young (2012)

The exhibition of Macau Days in Adelaide in 2017 was accompanied by a book of the same name, featuring a collaboration principally between artist John Young and writer Brian Castro, both Hong Kong-born but now resident in Australia. This trilingual book cannot be described as a catalogue as such, but as both a literary amplification of the exhibition and also as a transformation of its spatial presence into a physical object, a keepsake of its phantasmagorical content.

The project enters a web of memory that signifies a discrete but ever-fading sense of the nature of an almost vanished Macanese culture. It does so through the senses and their incorporation into what Young has termed “the history of benevolence” as represented by six historical (and mythological) figures whose migratory presence inflect and inscribe this culture. Those “placed under the poetic microscope are a mixture of saints and sinners” who paradoxically provide structure to the overall concept, which insists upon its presentation as a capturing of an amorphous dream.

The six figures are the Chinese sea goddess Mazu, and a series of what appears to be ghostly fathers: Portuguese poet Luis Vaz de Camoes, Chinese painter and poet Wu Li, Court artist and Italian Jesuit, Giuseppe Castiglione, Portuguese writer and Japanophile, Wenceslau de Moraes and Portuguese poet Camilo Pessanha. In the exhibition, Young’s large paintings of Mazu, with their interplay of sculptural depth and dynamic calligraphic line, the blackboard paintings with the overlay of text and the reconstituted historical photographs mingle with an immersive soundscape by composer Luke Harrald. The soundscape features random sounds of Macau and the poems of Brian Castro read in three languages. In the book, the phenomena of sound is transferred into text. In this typographically sophisticated volume designed by John Warwicker, Castro’s English language poems rest on a white background, the italicised Portuguese versions on black and the Chinese on gold.

Castro’s incisive portraits of each figure, their characteristics addressed in a rather wistful, light-hearted tone, and at a good distance from the gloom of moral and cultural disapproval, receive emblematic status through the bestowal upon them of a gift of a particular Macanese dish (recipe included), sumptuously photographed by Young. Here memory, residing in the blackboard paintings and photographs, morph into the Proustian realm of recall retrieved through taste. Castro writes that “I’ve never wandered far from the idea that food isn’t so much an aphrodisiac but a great cure for amnesia and a formation of literary style.” He recalls his father’s love of preparing shrimp paste, or balichao: “He simmered everything until old Mrs Harris complained in falsetto from the far end of our apartment block. She was his oven clock.” In “Entrée,” he writes “wine and forgetting, grief uncorked, / tasted briefly of Proust’s Cambray,” “mingling smells of kitchen and musk / with recipes of how / we used to live in old Macau / dining in bittersweet memory.”

Childhood memories connect to one of those poets from “the history of benevolence,” Luis Vaz de Camoes (“a barbarian armoured in melancholia”) through the recollection of the absent and occasionally visible parent reading from The Lusiads over dinner. Recollecting how an imagined affinity can inform identity, Castro writes “He identified so much with Camoes’ heroic verse that he lived the life of Camoes, participating in illicit romances and street brawls that lead to his periodic loss of employment.”

John Young refers in an interview to the importance to his practice of the geopoetics of Scottish poet and French resident, Kenneth White, and by extension the “nomadism” of Charles Olsen. The situating of Macau as a marginal, almost exemplary example of the periphery is refracted, almost subverted here by an engagement with the complexity of what constitutes the here and the there, and the web of exchange between East and West. Presentation, adaption and recuperation have seen artistic variations glimmer in different guises. In Young’s “Marienbad,” the painting appears as an evocation of a dream. Within the referencing to the Macau casino, and the drifting protagonists in Alain Resnais’ film, Last Year in Marienbad, a cabinet of family treasures signal a past barely held in a fading negative, and framed in the foreground by an arrangement of gently dispersing flowers. The final sequence of photographs in Macau Days is a re-worked set by Young of photographs by Aleko E Lilius, I sailed with Chinese pirates (1920). These luminous portraits of female pirates and their entourage reflect the wild and often ungovernable nature of this entrepot, of a region of often fluid demarcation.

The final image in Macau Days is a small colour photograph of Young and Castro, afloat on a gondola in the interior waterways of the Venice casino in Macau. They smile, as if knowing that this is not all they have.

![]()

Jennifer Mackenzie is a poet and reviewer, focusing on writing from and about the Asian region. Her most recent publication is Borobudur and Other Poems (Lontar, Jakarta 2012) and she has presented her work at a number of festivals and conferences, including the Ubud, Irrawaddy and Makassar festivals. In 2015, she had a residency at Seoul Artspace Yeonhui, and currently she is working on a poetic exegesis of the life and work of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, and also a collection of essays, Writing the Continent.