by Gabrielle Flores

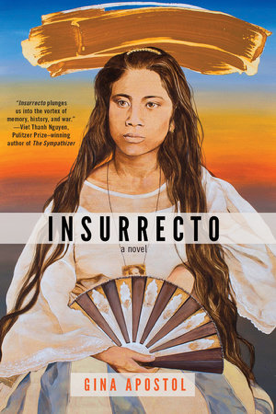

Gina Apostol, Insurrecto, Soho Press, 2018. 336 pgs.

It’s hard to begin a review for a novel that begins many, many, many times over. Viet Thanh Nguyen describes Gina Apostol’s Insurrecto as “meta-fictional, meta-cinematic, even meta-meta,” describing the labyrinth of meaning-making and obfuscation that forms the bedrock of the text.

Set largely in the present day, Insurrecto focuses on a filmmaker and a translator who set off to shoot a film on the Balangiga massacre of 1901, a long-forgotten episode of the Philippine-American war. What sounds like a road-trip movie gets kookier as the Magsalin, the translator, writes another version of director Chiara Brasi’s script.

Insurrecto is divided into two parts. “Part One, A Mystery” establishes the main plot of the story, while “Part Two, Duel Scripts” shuffles back and forth between Magsalin and Chiara’s dual scripts. Notice the pun in the title of part two?

“I presented the possibilities of translation,” Magsalin says when confronted by Chiara.

That this scene has been quoted by dozens of book reviews since then speaks to the growing trend of novelists reclaiming their own narratives, wresting them from those in control. John Powers, writing for NPR, uses his fascination with Western empires as his entry point into the novel, proving that Insurrecto works best as a re-introduction to Filipino identity and culture in this current World Literature boom.

Apostol uses the whole gamut of literary gimmicks to destabilise the reading experience, from chapters that are numbered out of order to a series of endnotes that are not so much expository as they are creative musings.

It’s hard to argue that this book will be read outside of the literati spheres. The out-of-order chapter numbers is a trick that quickly grows tired. The fact that the titles of all the chapter ones come together to form a sentence is an observation only a keen reader (or someone writing a book review) would try and look up, let alone find interesting.

These gimmicks could be read as concessions to the larger literary market that Insurrecto wants to fit into. The question of audience naturally comes up with regard to postcolonial novels—who is the book trying to reach?

Reading Insurrecto in the Philippines, you’d expect a more definitive re-take on this period of history. “Anti-imperialists are touchy people,” Apostol writes, acknowledging the pressure put on authors like her to set the record straight.

Apostol, however, isn’t in the business of setting anything straight; she wants to show just how fractured and messy the history of the Philippines is.

Insurrecto is heir to a Philippines whose history has been contested and rewritten many times over, where people like Magsalin and Chiara have to sift through different versions of a story told long ago.

It’s fitting that Magsalin and Chiara are positioned as outsiders, their relationship with the Philippines mediated by experiences outside.

Chiara knows the Philippines in hazy childhood recollections: she grew up in the Philippines while her father Ludo directed his final film. Magsalin is quick to dismiss Chiara’s project symptom of white guilt. Call it a projection of one’s own flaws: Magsalin is also incredibly detached from the karaoke-singing culture that her family has, and is using this opportunity to atone for her leaving.

According to Magsalin, “The immigrant’s tale is also one of agency, you know, not just misery … instead of returning, through the years, every time she finds a book about the Philippines, on AbeBooks or Amazon, she buys it.” She’s part of the large Filipino diaspora, whose identity is a cross between homestyle moral values and a more liberal outlook that comes with living elsewhere and growing up alongside the internet.

Through these observers, Apostol points out the way in which being in-between identities provides “insight that was useless, on one hand, but terribly urgent on the other.” From Chiara’s botched Bayang Magiliw to Magsalin’s theories regarding the fascination behind Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, Apostol is sensitive to the fact that all this head knowledge doesn’t easily translate into a sense of belonging.

The Philippines provides the perfect backdrop for Chiara’s and Magsalin’s personal journeys. From the backlit bakeries of Cubao to a tourist-trap restaurant on the way to Balangiga, the Philippines of Insurrecto is a frenzy. It’s a place where people pay to watch midgets box in the city’s financial district, where Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” is a mainstay in at least twenty karaoke booths on any given night and where young Filipino citizens are becoming engrossed in indie films.

This portrayal of the Philippines is where some readers might feel a little duped. Mentions of Duterte are few and far between, operating as background noise. There’s a drive-by shooting later on in the novel that is over just as quickly as it begun: it’s a clear reference to Duterte’s drug wars, but one that seems tacked on for the sake of being relevant.

What always stays relevant, though, is the Filipino penchant for humour. “The humorous self, the good humour with which Filipinos have risen to be a vital nation … just really makes me want to write,” Apostol said in an interview with CNN Philippines, which Insurrecto makes clear.

Case in point is “By the Time They Pass Oras” (one of the book’s many chapter ones). It’s a delicious play on words, “oras” being the Tagalog word for “time” but also the name of a city in Bicol. It’s hard to talk about being Filipino without mentioning the humour that fuels everyday interactions. The novel is brimming with jokes such as this precisely because the Philippines itself is such a punny country.

For all the stylistic concessions and nods to a more learned crowd, there’s no denying that Apostol can write. She’s good with words and knows how to use them, as adept with picking out puns as she is writing statements that kick you right in the chest.

Insurrecto is the kind of novel where you can tell just how much fun the author had writing it. From the tongue-in-cheek footnotes to the shifting narratives, Apostol—under the premise of revisiting history—showcases her literary talent, no holds barred.

This off-kilter-super-meta narrative is, perhaps, the only way to describe what it’s like to live in the Philippines. By arguing that there’s a wealth of Filipino history that has yet to be reckoned with, Apostol opens these episodes up to interpretation, to different points of view.

![]()

Gabrielle Flores graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Literature and Creative Writing from New York University Abu Dhabi, and is now based in Manila. She’s interested in the Filipino diaspora, the intersection of postcolonialism and World Literature, translation studies, and food. Thinking and writing about it, sure, but mostly just eating it.