by Ophelia Tung Ho Yiu

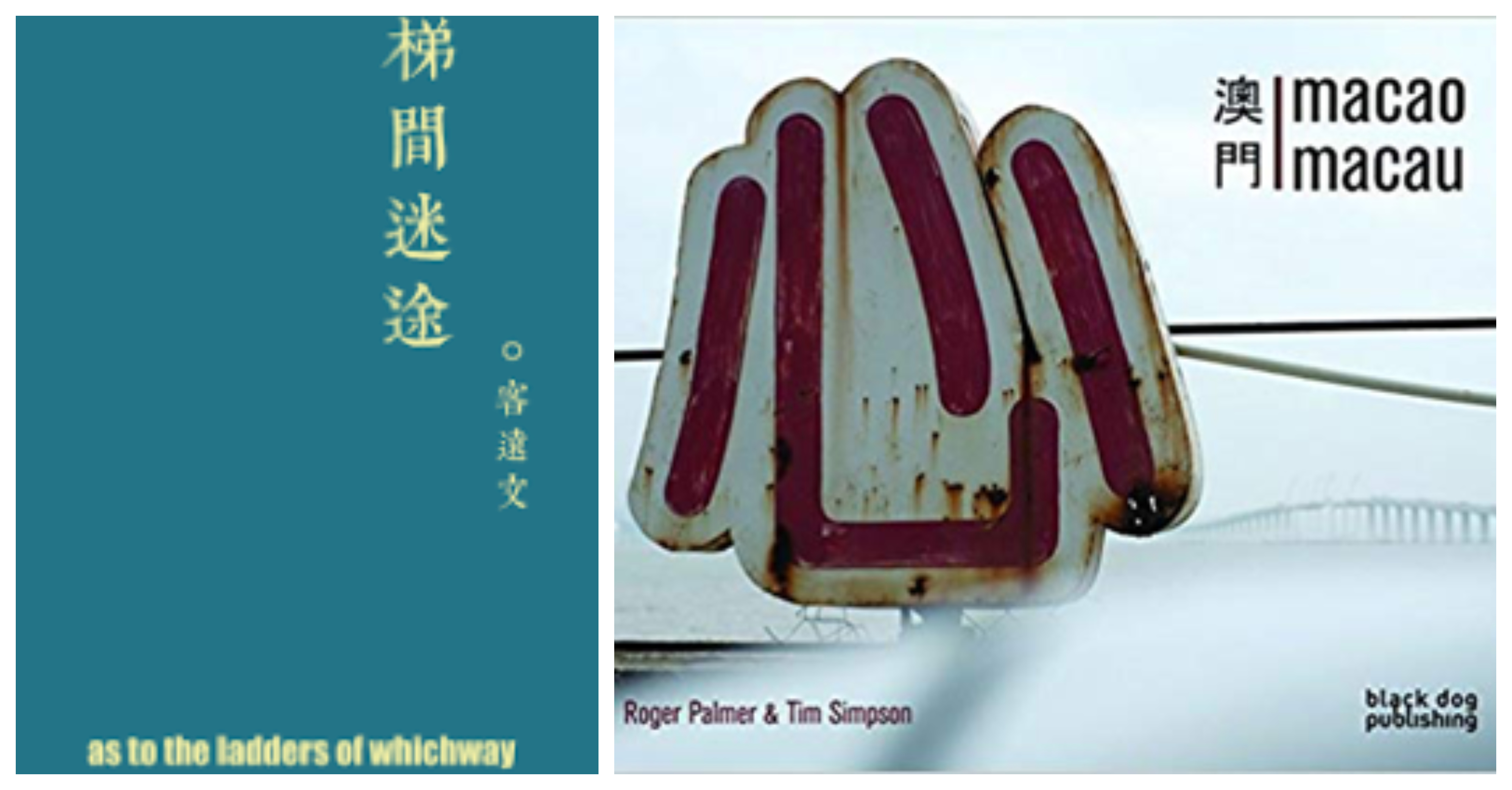

❀ Kit Kelen, As to the ladders of whichway, ASM, 2014. 165 pgs.

❀ Roger Palmer and Tim Simpson, macao macau, Black Dog Publishing, 2014. 101 pgs.

I have to admit—I was slightly perplexed when I was approached to write a review for Kit Kelen’s As to the ladders of whichway and Roger Palmer and Tim Simpson’s macao macau, for the editorial aesthetics and genres of these two books provide considerably different vibes. Kelen’s candid depiction of modern Macau is here juxtaposed with Palmer’s urban landscape photography and Simpson’s essays on the historical and post-colonial development of the city. With Kelen’s abstract yet heartfelt paintings and poetry revolving around themes of life and emotion, his book emerges as a peculiarly intangible yet mesmerising work that invites readers to read between the lines for deeper reflection. Despite my initial puzzlement, I ultimately managed to put the pieces together as I started to engage with the two books. In spite of all their apparent differences, As to the ladders of whichway and macao macau unite in their common sentiment of displacement and melancholy.

In As to the ladders of whichway, Kelen showcases the emotional depth of his writing by translating the sense of desolation and displacement into his work. This sense of loss and perplexity is vividly stated in the title of the collection, for one can easily envision the feeling of pursuing the correct and righteous path, only to be landed onto stairs that lead to anywhere and nowhere.

The raw sentiment of getting lost and yearning to be found is amply expressed in Kelen’s poems about various scenarios and aspects of life, some of which include his dialogues with other poets on mortality (“Celan,” “on the third planet – after Szymborska”), as well as his somber reflections on the passing of time and the fleeting nature of humanity (“when we were young,” “the end of things come after us”). I was particularly taken by “boy’s own death,” in which Kelen transforms a sense of sorrow towards the unspecified demise of a boy into a profound debate on mortality, religion and memory. Attempting to find a way to make sense of the boy’s death, the narrator dwells between the “atheist’s dark certainty nothing” after a mortal’s passing and the “searing (Christian) faith wishing” of an eternal afterlife, evoking a sense of loss and hollowness in this tragic event. He further mourns the fragility and temporality of life when it is placed within “the vastness, the sparseness” of the universe.

Kelen, however, transcends the melancholy of the perpetual loss and misplacement of life with one final wishful enigma on transience and immortality. Although the death of the boy may be as insignificant as the dissolution of atoms, the disintegration of his life allows him to become “part of the big picture,” granting him the opportunity to be closer to “that truth beyond of every frontier” and embark on a new adventure in death. In “boy’s own death,” Kelen sticks to the overarching theme and style of the book, demonstrating an insightful vulnerability as he tries to come to terms with anguish and mourning. He expresses the disorientation and melancholy of treading through one’s existence without any directions, yet nevertheless finds hopefulness in ultimately discovering a path, whether in the form of the imagination of happiness or the reconciliation of emotions.

In contrast, Palmer and Simpson tackle the theme of displacement from a geographical perspective in macao macau. They tell the lesser known story of Macau’s spatial and temporal dislocation in the age of post-colonialism and globalsation, which can be found behind the representation of the city as a glamorous cosmopolis. In their respective photographs and essays, they evoke a deep sense of suspicion and melancholy towards the future of the city.

In his two photographic series titled Pearl and Macao Macau, Palmer offers a unique angle that speculates about and inquires into the fleeting and transitory character of urban experience. His images are weaved seamlessly into Simpson’s essays on the development of the city, which helpfully provide the historical, political, social and post-colonial context necessary to fully understand and appreciate Palmer’s photos. In Pearl and Macao Macau, Palmer dispels with Macau’s splendid façade by revealing the disillusionment behind its pretense.

I was especially intrigued by MM#14 in the Macao Macau series, which depicts the eeriness of the social plasticity and porosity of a city undergoing urbanisation and the development of its casino tourism industry. Taken through a display window, MM#14 reflects the affluent, prosperous side of Macau’s urban cityscape. However, intentional overexposure provides the photo with a greyscale filter, thus endowing the buildings with a phantasmagoric, uncanny ambiance that transforms these emblems of modernity into cold, haunting outlines that resemble x-rays and convey a sense of bleakness and desolation. This mood is further highlighted by the shadows of everyday street views reflected on the glass, the blurriness of the silhouettes behind the towers adding to the psychedelia of the images. Incorporating Simpson’s critique of Macau’s loss of agency and authenticity, macao macau offers a more pessimistic view to the city’s development by channeling an unsettling sense of weariness, melancholy and loss.

In As to the ladders of whichway and macao macau, Kit Kelen and Robert Palmer and Tim Simpson offer multiple perspectives on the themes of displacement and melancholy by utilising their respective mediums. Kelen’s exquisitely poetry depicts the vulnerability and emotional torture of the soul-awakening journeys necessary to make sense of the intricacy of life, while Palmer and Simpson acutely express their cynicism towards the development of Macau with images and words as their witness. While Kelen’s work provides a therapeutic experience which invites readers to empathise and recuperate, Palmer and Simpson’s photography and essays encourage us to ponder the larger issues facing Macau.

![]()

Ophelia Tung Ho Yiu is a postgraduate research student at the Department of English at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). Upon acquiring a Bachelor of Arts in English with a minor in Cultural Studies at CUHK, and a Master of Arts in Literary and Cultural Studies at the University of Hong Kong, she now proceeds to obtain her Master of Philosophy in English Literary Studies at CUHK. Her MPhil research focuses on the tension between the authorship and readership of Jane Austen in a post-structuralist and post-modernist age of fandom and popular culture.