by James Au Kin-Pong

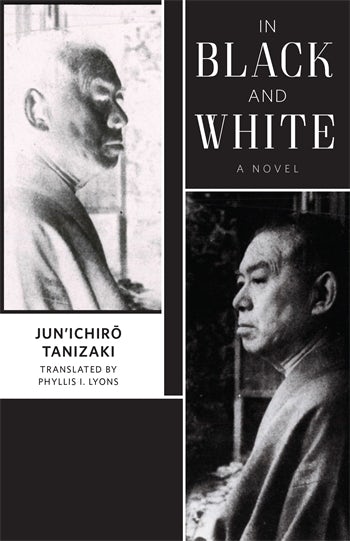

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (author), Phyllis I. Lyons (translator), In Black and White, Columbia University Press, 2018. 256 pgs.

Originally serialised in a several Japanese newspapers in 1928, In Black and White is more than a psychological novel as it provokes the reader from time to time to rethink the intricate relationship between “fiction” and “reality.” In it, Mizuno, the writer of a mystery novel, has completed a manuscript and sent it to The People for their April issue. The fictional character in this story, Codama, is modelled on a real figure Cojima, who is later found murdered. When Mizuno discovers that he has wrongly written Cojima (instead of Codama) in his manuscript, he nervously calls the editor to rectify the mistake, but to no avail. Nearly psychotic, Mizumo fears that Cojima will actually be killed just as Codama is in the story, and that he himself will be convicted of the murder. He attempts to seek ways to keep himself from being suspected, only to find unbelievably that reality is approaching his own story so closely that he at times becomes perplexed trying to distinguish between what is real and what is not. “Shadow Man” in Mizuno’s story and the woman with whom he develops a sexual relationship also add complexity to the distinction.

Before reading Lyons’s translated version, I searched online for a pocket-sized Japanese version (or Bunkobon in Japanese) of the same story, but unlike Tanizaki’s other novels such as Naomi (1924) and Some Prefer Nettles (1929), In Black and White exists only as a cell phone-book, implying its relatively low popularity and recognition compared to his other masterpieces. In the end, I borrowed the thirteenth volume of The Complete Works of Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, which contains the story.

My first impression while reading the original Japanese was its resemblance with Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s In a Grove (1922) (which was adapted into the movie Rashōmon directed by Akira Kurosawa), since both works deal metaphysically with the issue of fiction and truth. But while the latter questions the existence of truth as all the suspects of a crime give contradictory testimonies, the former asks readers to re-examine the distance between the author and the characters of the story.

A second read, this time in English, allowed me to appreciate it even more. Lyons’s decent translation almost allows English readers to access what their Japanese counterparts can. There were, I imagine, a few parts which were exceptionally hard to translate. The episode where Mizuno frets over the naming of the character in the story is one example. Another example can be found in Mizuno’s monologues, although the translator does well to retain their psychotic mood.

The translator’s afterword offers the reader various possibilities for reading the novel, since she provides a detailed background about the author’s life and his connections with his contemporaries, especially Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, and about the literary and cultural landscape of Japan in the 1920s. The reader might be justified in wondering to what extent In Black and White addresses the issue of whether an autobiographical novels/I-novel, or Shishōsetsu—a genre of confessional literature in which most events are said to be based on the author’s experience and which were popular in 1920s Japan—can reflect real life. To put it in simpler terms, it seems that this plot-within-the-plot story is an attempt to ask how autonomous a literary work can be, a debate which is also concerned with the social and aesthetic value of literature.

If one must be critical of Lyons’s translation, it would be that this book may aim at a reader who already possesses some basic knowledge of Japanese culture because some words such as tabi-clad foot and oden stall are left italicised without further explanation. It would have been better if an endnote had been provided for those who wished to understand more about the meaning and cultural context behind each untranslated word.

I also found awkward the treatment of the German terms uttered by the woman with whom Mizuno later has an affair. It seems, at first sight, that the protagonist does know some German, but it becomes clear that he does not as the story proceeds. In contrast, in the original version, Katakana—a kind of Japanese writing—is employed to appropriate the sound of the foreign language and make it clear that Mizuno does not understand what is being said. The translator should not be blamed for this awkwardness, though, since there seems to be no alternative.

However, Lyons should be given credit for introducing readers to this lesser-known Tanizaki novel. Her translation draws the reader’s attention to this fantastic masterpiece, one which is comparable in quality to his other works, such as Naomi, Some Prefer Nettles and The Key.

![]()

James Au Kin-Pong is a Master’s graduate of both Hong Kong Baptist University and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London. He is currently writing his PhD thesis about the relation between history and literature through close readings of Japanese historical narratives in the 1960s. His research interests include Asian literatures, comparative literature, historical narratives and modern poetry. During his leisure time, he writes poetry and fiction in various languages, and translates poems into English. He is teaching English and literature in English respectively at Salesio Polytechnic College and Sophia University.

James Au Kin-Pong is a Master’s graduate of both Hong Kong Baptist University and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London. He is currently writing his PhD thesis about the relation between history and literature through close readings of Japanese historical narratives in the 1960s. His research interests include Asian literatures, comparative literature, historical narratives and modern poetry. During his leisure time, he writes poetry and fiction in various languages, and translates poems into English. He is teaching English and literature in English respectively at Salesio Polytechnic College and Sophia University.