by Lindsay Shen

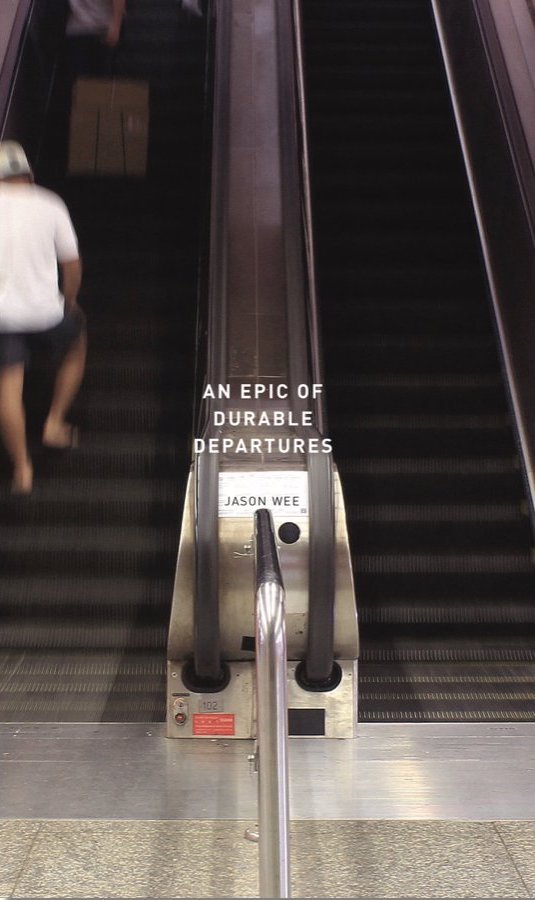

Jason Wee, An Epic of Durable Departures, Math Paper Press, 2018. 85 pgs.

Jason Wee’s Epic of Durable Departures is convincing argument that the choice to live well, to “Preserve Faith, Share Joy, Face Death,” is an epic-worthy feat, especially when the end of that life is shaped by disabling illness. Dedicated to the Singapore performance artist Lee Wen, whose words I’ve quoted above form the book’s epigraph, this cycle of forty-three poems stands as the record of a friendship between two artists and as an extended goodbye to Wen, who died in March of 2019.

An artist and curator as well as a poet, Wee manipulates literary form in ways that are visually as well as structurally satisfying. This epic begins with an epilogue and, through a backwards narrative arc, concludes with an introduction. The route of this friendship is marked by Wen’s physical decline from Parkinson’s, an especially debilitating disease for an artist who used his body to critique social norms and who was recognised in 2005 with Singapore’s Cultural Medallion, the city-state’s highest arts award. Wee’s contemporary riffs on the collaborative renga form of poetry suggest fragments of conversations recorded, remembered, imagined and, in the poem “Epilogue,” poignantly one-sided as Wee anticipates his loss: “I write of a coast, the changing of it, // every year these goshawks make me an immigrant / without pass or power in their high places.”

The trajectory of grief isn’t charted from a safe distance (Wen was living when this collection was published) yet Wee wields a level of artistic control that allows an observation of physical frailty almost as dispassionate as a hospital record: “Your skin, fetal / as a spine’s exposed stitching” (“Waiting Room Sonnet”) or “Today we admit / drawing is gone. Somehow / ‘You can’t walk’ is easier” (“The Sunset’s A Sour Peach”). The disrupted renga form of “The Names in the Forest Are Not Our Names” itself mimics the disruptions of the central nervous system:

The prey in the forest

It got to a point

have a name for ‘cloud’, it is

when I felt like having no

the name for a wound

limbs at all …

At other times, Wee switches to metaphor, displacing illness’s intrusions onto the werewolf’s involuntary transformations:

The subcutaneous air

trapped against skin’s high walls

freshly graffitied

with a cool desire

for a breach … (“Lycanthrope”)

Whether expansive or restrained, tied to the mundane moment or invoking myth, Wee’s concise poetic form allows him to script “description / past the look-away point” (“Lining The Pants”) and to express rather than release anticipatory grief.

The choice to work with reverse time also shows us that the stages of grief are unstageable, a realisation conveyed at its best in the tragi-comic “Being All Kubler-Ross at Your Wake” with its bald opening:

The first stage is cheese.

Before that is knowing

who to call for flowers.

Before that the sum of friendship and

funeral equals chrysanthemum.

Although Lee Wen remains the subject of this undeniably elegiac collection, eulogies for other artists and references to ghosts remind us of the littoral space we all inhabit and also that the trajectory of our journey through life may be anything but orderly. Wee reminds us that departure is one of the few durable facts of our existence.

Towards the end of the collection, “Time Machine” pulls us beguilingly backwards:

Reach any beginning. We both know,

groundhog, winter has only begun.

Molted shells slide back to flesh

Despite his insistence on mortality, Wee’s pleasure in the sensory world is like a convincing memento mori still-life painting, heaped with fruits and flowers just this edge of decay. It is as an artist as well as a poet that Wee can write in the same poem:

metaphor disappears

when all things touch,

my hand tightly on yours,

that thought astringent as

the bitter skin of walnuts

That the tangible world underpins this collection seems entirely appropriate for a poet who is also a visual artist trained in photography and philosophy. The work’s satisfying physicality is also testament to Lee Wen, whose series The Journey of a Yellow Man gained the artist international exposure for his use of performance art to explore issues of race, censorship, social justice and spirituality. While An Epic of Durable Departures takes its place within a long and diverse tradition of poetry on the subject of illness, this collection also provides glimpses into Singapore’s multi-cultural, multi-lingual art and literary scenes. We see Wen perform one of his seminal pieces, covered in yellow paint, curled foetus-like in a basin; we traverse gallery openings, exhibitions and award parties. Both artists have been instrumental in supporting the work of young artists in Singapore, while moving beyond identity politics into a discourse with international contemporary art movements. Wee is the founder of Grey Projects, an artists’ space and platform that has promoted artistic exchange with China, Spain, Taiwan and Colombia. In addition to two previous works, The Monsters Between Us and My Suit (both Math Paper Press), he is founding editor of the poetry journal Softblow, which publishes a mix of Singaporean and international poets.

This collection is grounded in the story of a friendship between two Singapore artists with a shared purpose. The sensory world it draws on, from pomelo fruit to albizia trees to street names, is subtropical. But like all good epics, this work has resonance far beyond its starting point.

![]()

Lindsay Shen is Director of Art Collections at Chapman University in Orange, California, where she also teaches the history of Asian art. She lived in China for eight years, teaching in Shanghai and also living in rural China. She is currently completing a book on Tianmushan, a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve where she lived for several years.