by David Haysom

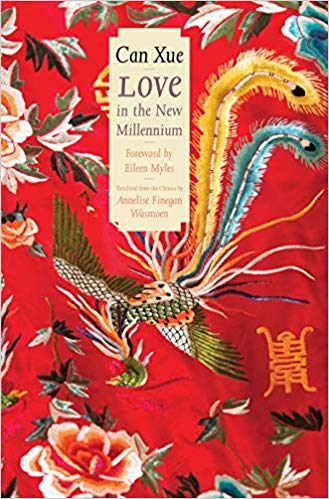

Can Xue (author), Annelise Finegan Wasmoen (translator), Love in the New Millennium, Yale University Press, 2018. 288 pgs.

Talking about the plot of a Can Xue novel is a futile exercise. Plot means a hierarchy of importance, but dramatic significance is spread evenly across Love in the New Millennium: a chance encounter with an acupuncturist on a plane carries the same weight as a traffic accident, and an encounter with a pair of angry pigs is no more or less meaningful than an attempted murder. Plot means suspense, but the only reason to keep turning these pages is to discover the next discrete moment of delightful absurdity. Plot means a relationship between cause and effect that does not exist in Can Xue’s fictional universes, where the reigning paradigm is the nonsense logic of dreams.

This extends to the novel’s protagonists—a group of women who have left their factory jobs to become sex workers, plus their assorted lovers—whose emotional reactions are often slightly out of sync with the actions that trigger them. Heartfelt congratulations is the appropriate response to an outpouring of woe; the ransack of a building by armed goons is cause for hilarity; the passions of an aggressive suitor are only further inflamed when his target stabs him in the arm with a pair of scissors. They pass the narrative between them as they whirl, like dancers at a ball, from one paramour to the next. The widow Cuilan falls in love with Wei Bo, a soap factory worker who ends up in prison despite not having committed any crime. Wei Bo has a fling with the beautiful, accident-prone A Si, before she gets involved with a shady opium dealer. Meanwhile, Wei Bo’s wife Xiao Yuan falls in love with a doctor after a chance encounter on a train, while Long Sixiang—another old flame of Wei Bo’s—has moved on from the unctuous antiques dealer Mr. You, and is now in a tempestuous relationship with a vulgar cement merchant named Lao Yong. It takes some time for any of these characters to assume solidity. Some of them acquire detailed biographies later on, but at first, they are slippery, insubstantial, even interchangeable—to each other, as well as to the reader. Identity is fluid: a character might be reincarnated, or forget who he is, or decide she is a doppelgänger duplicate of herself, or suddenly turn into a panther. “After working in this business for a while,” A Si reflects at one point, “we know that a person has many faces.”

More concrete and vividly realised are the settings, and it is the movement back and forth between them that provides the book with propulsion. Chapters often begin in the city, where the rules of reality appear more rigid, before veering into the surreal once we journey (by train, by taxi or through one of the many caves and tunnels that thread the novel) to a rural location. When the first chapter climaxes in a visit to Cuilan’s home in the countryside, it is not long before fireballs are dancing across the sky, bodies are slumping out of trees and a duelling green-eyed tinker becomes an electrified silver statue. These locations are mostly lacking in geographical specificity, with occasional references to qigong, the Monkey King, and Maotai liquor providing a light veneer of local texture. Nevertheless, as the thematic concerns of the novel are gradually revealed through a process of repetition, it becomes apparent that Love in the New Millennium is tapping into some of the same ideas that have motivated much of contemporary Chinese literature: the urban-rural divide, the sense of dislocation that migration causes and the meaning of family in such circumstances. “There’s actually no difference between the city and the countryside,” according to one character, “or, if I had to say what difference there is, then it’s that the city is even more lonesome than the country.” A Si keeps reliving the circumstances of her father’s death. Wei Bo is described as a rootless character, because he has no idea where his ancestral home is located (having been blindfolded by his father every time they made the trip). Later, one of his fellow prisoners will catch a tantalising glimpse of his hometown reflected in the water of a creek.

Like a lot of contemporary Chinese authors, Can Xue has taken in the influence of Kafka, but she has assimilated it more thoroughly than many of her peers. Her closest counterpart in contemporary literature is perhaps the Argentinian author César Aira, with whom she shares an improvisational approach to writing: both have stated that they move only forwards through their manuscripts, never stopping to edit or revise. Can Xue herself has suggested that a familiarity with the works of Dante, Goethe and Tolstoy is essential for any reader hoping to understand Love in the New Millennium. It is tempting to see a stab of sarcasm in the book’s title, but elsewhere in the same interview Can Xue insists that “every character in the novel is beautiful, incredibly beautiful”—perhaps even holy. Also worth noting is the fact that the book’s original Chinese title (新世纪爱情故事) could be translated as “Love Stories of the New Millennium,” which feels less like a grandiose declaration of intent. Annelise Finegan Wasmoen’s translation perfectly conveys the atmosphere of the text itself; a particular strength is the way it captures the varying focus of Can Xue’s gaze, which can oscillate between fine-grained intensity and a nondescript blur (the description of animals, in particular, is often vague: they may be “as big as a goat, but not a goat,” or simply a “fantastic beast”)—no mean feat in a text that makes it difficult to even distinguish between the literal and the figurative.

![]()

Dave Haysom has been translating, editing, and writing about contemporary Chinese literature since 2012. Joint managing editor of Pathlight from 2014 to 2018, he has recently translated novels by Feng Tang, Li Er, and Xu Zechen. His portfolio is online at spittingdog.net.