by Jason S Polley

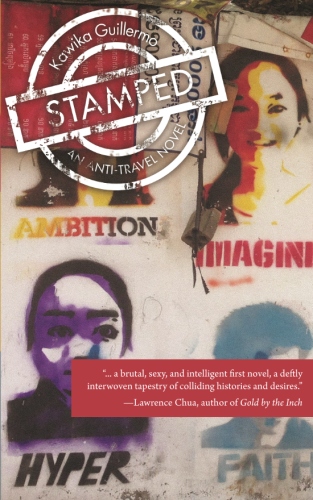

Kawika Guillermo, Stamped: An Anti-travel Novel, Westphalia, 2018. 360 pgs.

He understood that need to escape, but did not expect this restless abandon; how travel can drive you, how it takes the wheel, propels you forward until the wind slaps off skin, drying organs like old leaves, cornering the spirit into the herded pressure of a heart promising to explode.

—Kawika Guillermo

The place: the balcony of the room on the top floor of the Monalisa Guesthouse in Leh, Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Leh is the Top of the World, not to be confused with the Himalayas themselves, known as the Roof of the World. Leh’s on the Silk Road in the highest motorable mountain passes on the globe—and, incidentally, Amazon’s highest elevation delivery point. Tibet’s to the east, Xinjiang’s to the north, Tajikistan’s to the northwest, Pakistan’s to the west and Hindu India’s to the south.

I’m reading the first novel of a former Hong Kong Baptist University colleague, who uses the nom de guerre Kawika Guillermo. Kawika is also the favourite name, of several chosen ones, when in drag, of Guillermo’s self-destructive protagonist Skyler, whose changing “look was a temporary refuge, a place to leap in and out like two selves, one ruled by the sun, the other the moon.” Unlike Gita Mehta’s Karma Cola (1979), which I first read on my first visit to the Indian subcontinent in 1997, Guillermo’s Stamped: An Anti-travel Novel doesn’t make me feel like, well, a hollow coloniser. By a coloniser I also mean a missionary, by which I really mean a sanctimonious, incorporated imperialist destined to smash the well-wrought urn of culture only to repackage and re-appropriate it. That whole Jesus down-your-throat evangelical hypocrisy. That whole Nirvana for 50 bucks bullshit, as Air India packaged it sans the qualifier four decades ago, so Mehta reminds us. But maybe I’m just older, less unaware and more careful. The pendulum just swung from idealist to cynic too swiftly under Mehta’s insightful influence. Twenty-one years later, I’m fragile in different ways. Guillermo’s characters, however, are still in their 20s.

In the first twelve days of this trip, I’ve recovered from a four-day migraine resulting from the combination of sunstroke in Old Delhi and cold rain in Srinagar; the loss of my new phone on a rickshaw between Old Srinagar’s Jama Masjid and a houseboat on Nigeen Lake and the crippling, purging effects of altitude sickness in the thin, desert air of Leh, which rests in the Himalayan foothills at 3500m above sea level. The long road trip here had me recalling Iqbal’s musings on “human endurance” in Kushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan (1956): “He would have described the journey as insufferable except that the limits to which human endurance could be stretched in India made the word meaningless.” Over my first few days in Leh, it felt like I was trying to breathe through a plastic bag, this especially after climbing the two—only two!—flights to my Monalisa enclave. On the southeast side of the Himalayas, Guillermo’s weary, slurring Skylar likewise suffers from “elevation sickness” while the expat posse drunkenly cavorts through Yunnan’s Lijiang.

But here I am. On my balcony. “Pops” Dilip, the 26-year-young Indian-born Nepali proprietor of the Monalisa, will join me to watch the World Cup semi-final tonight. He’s cheering for England. Me, Croatia. If England wins, I get to punch him in the face. If the Croats do, he gets three rapid fists to my gut. He too likes jokes. And he and the smiling cook Dolma make to-die-for Ladakhi momos and pakthuk, the latter a local variant of Tibetan thukpa. Alongside sweet lassis, ginger tea, bananas, soda water, dosas and throat lozenges, this is about all I consume—save for when a smiling Ladakhi offers me a single Gold Flake or Four Square cigarette. Amazingly, beer, a quotidian escape in my Key Performance Indicator-determined Hong Kong incarnation, has been drained from my diet. Tout court. Totally. Inshallah. Not even an afterthought—but here I am lingering on the fermented hops that water and Thumsup so effortlessly superseded.

And here I am at once hearing two imams’ azans, Tibetan Buddhist Ladakhi om mani pae mey huns, goat bleats, cow lows (they like being hand-fed Kashmiri apples), sparrow chirps, donkey tiptoes (they like bananas, peels and all), magpie caws, jeep horns (“Blow Horn”/ “Use dipper at night”), Royal Enfield Classic, Bullet and Himalayan engines and, naturally, Despacito on forever-peat.

But enveloping it all, or at what the late William H Gass might have called “the heart of the heart” of it all, I hear the smiles. Yes, you hear the smiles here in almost every julley. Julley means hello, goodbye and thank-you in Ladakhi. I hear my mother smiling too—I’m thousands of metres closer to her resting place above the sheltering sky. Here I am being beneath her un-being. And, finally still, and stilled, I’ve stopped longing. However, Guillermo’s “desperate characters,” to borrow Paula Fox’s 1970 novel title, can’t escape the restless abandon that propels them forward, and downward. They can’t be stilled. Nor can they slough off the cynicism that Mehta’s Karma Cola justifies so well. Guillermo himself, so he relayed to me, left Mehta’s book “on a bus somewhere in India.” The disaffection of Guillermo’s characters, I think, is just as much the price of distrustful youth as it is the wage of self-imposed estrangement from the Asians around them. Drunken sarcasm and unserious sex do not—just cannot—count.

❀❀❀

Guillermo’s down-and-out antihero Skylar—after travelling, and sporadically working, in places including Bangkok, Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Singapore, Ubud, Macau, Yangshuo, Dali, Chengdu and Manila—resurfaces from a month-long-plus stay in a Seoul sauna to reconnoiter in Goa with fellow American flaneur Sophea. The one caveat for this nascent-Obama-era early-20s transgressive part-time couple, however, is “none of that travel-helps-you-find-yourself bullshit.”

Unlike their similarly young—but white—fellow American flaneurs Melanie (who’s CCTV-recorded Seoul sexcapades make newspaper headlines) and Arthur (whose 15-years-older Chinese wife absconds with their infant son from “skyscraper canyon” Shanghai to anonymous Nanjing), the Cambodian-American Sophea’s and the Filipino-Hawaiian Skylar’s “karma chameleon shit” can “fit no stamp.” Sophea and Skylar, whose interiority interpellates tentative readerly sympathy through the second-person, know all-to-well that “this would all be different if you were white.” “White,” Skylar, in a moment of sober pause, had earlier reflected, “he was just some dumb tourist, no threat to anyone. Brown, he could only wonder.”

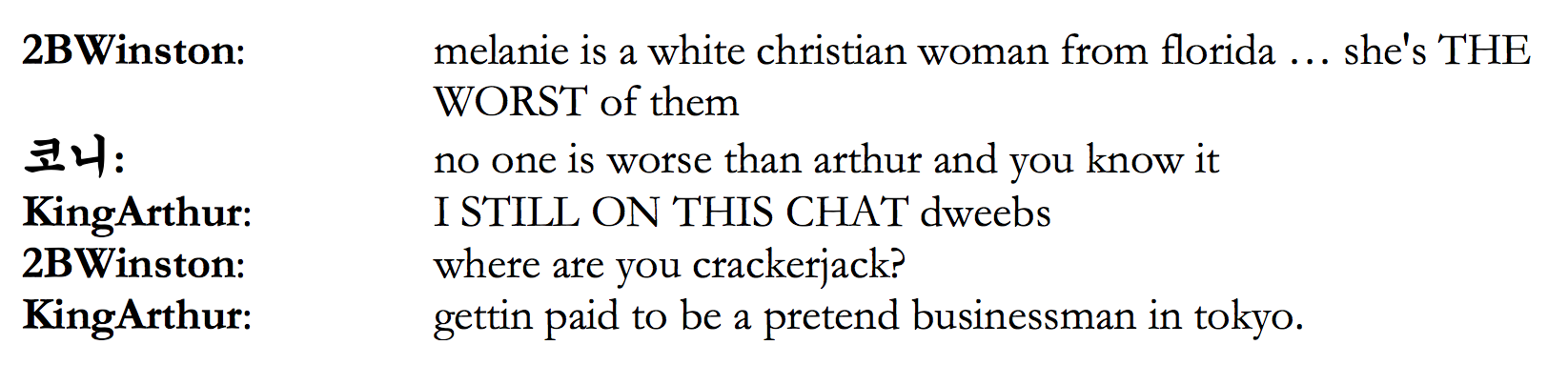

By novel’s end, Skylar fully understands that “People will either get what you’re doing, or label you something convenient.” “White,” of course, too is “convenient.” Especially evident on the US expats’ “Flaneurs Spacechat,” Arthur and Melanie are playfully vilified as de facto stakeholders of white privilege and racism:

Despite any privileges, Melanie and Arthur are as lost and damaged and disillusioned as Skylar, Sophea, Korean-American Connie and Japanese-Pinoy army-base-brat Winston. The self-styled flaneurs understand that these “whites” too have their roles, ones echoing the whiteness South Koreans weirdly champion by way of cosmetic surgery and western brand-name accessories, as Connie regrets upon realising Chun Hye’s “skill with an umbrella” (Chun Hye expertly eludes any visible effects from a fortnight of Cebu sun) and as Skylar laments when his Korean students gift him “whitening cream” (which he “threw … back in their faces”).

As young, flawed and disenchanted as these white and brown flaneurs are, they embrace a self-consciousness that recognises the disgusting irony of Kuta, Bali, where wandering “groups of large Aussie men casually dressed in the latest genocide of Polynesian tattoos and tank tops that carried a large red map of Australia with the words ‘Fuck off, we’re full.'” Skylar, and thus the reader, learns to “categorise” Arthur’s emblematic “anxious hyperactivity,” “vulgarities” and “inhibitions as slapstick entertainment”—and not the “fashionably dirty and ragged” fashion and self-fashioning of tourists “cloaked with that sheik pedophile style.” Cynical, aware and as alive to possibility as to its doppelgänger depravity, each member of the motley collective recognises how “Local [only] becomes another word for servants. It was the same in Vegas and Hawai’i.”

❀❀❀

The viewer/reader of Wallace Shawn’s one act, one-actor play The Fever (1990) cannot help but take the author-actor’s words personally. Shawn, who originally performed the piece to small groups in small venues, such as apartments, welcomed the frustrated and conflicted responses of his audiences. These corrosive reactions proved contiguous to the malarial fever the player’s travels and travails inflict upon him. The reflexive drama, which can be performed enveloping a toilet bowl or collapsed at a dining table, literally speaks to the hypocrisy of cosmopolitan urbanites eating fish and drinking wine while human brethren in less-privileged locales expire from torture, starvation and (other) political oppressions. Shawn masterfully, and chillingly, makes us all guilty; he shows us all to be complicit colonising elites. Shawn illustrates this in a comparable way to Peter Singer, whose moral philosophy exposes what he calls our “conditioned ethical blindness.” Singer and Shawn ask us to think about and act upon that which we typically refuse even to think about, let alone for-real act upon.

Kawika Guillermo’s first novel places him in the company of evocative and moving agents like Singer and Shawn. Whether or not you’re a traveller, or jaded, or young, or a cynic, you’ll end up rooting for Guillermo’s restless, escapist characters—this, in spite of their flaws and ressentiments. It’s on account of Guillermo’s expertly crafted and credible young adult fragility, one that will leave readers and re-readers amused, amazed, aghast, bored, bewildered and laughing out loud in turn, that readers will be compelled to look inward in order to improve their understandings of (the plights of) others. Guillermo’s ur-millennial misfit cast makes it plain that the author knows his shit. Like his cross-purposed characters, Guillermo knows South Asia, its sex, its sexes, its allures, its pratfalls, its clichés. Add Walter Benjamin to this connaissance. Add Julia Kristeva. Add a ghost. Add three dozen Asian cities. Add a couple handfuls of languages. And add tantalising entanglements in various sex zones of ill repute.

Above all this, Guillermo will have “you” return to your very own self-placement in these always-already placed places. What would you do? Or: what have you done? What should you do? What can—or could be—undone? Not all that is solid melts into air. There’s always, always something. And Guillermo will leave you grasping to embrace this tangible, worthwhile something, this personal place beyond the fever of escape.

![]()

Jason S Polley is associate professor of literary journalism, comics, and post-structuralism at Hong Kong Baptist University. Since his BA in English and Religious Studies at the University of Lethbridge he has lived and studied in places including China, Canada, Colombia, India, Bangladesh, Laos, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. He divides his time between reading, scuba diving, running, practicing yoga, and skateboarding. His research interests include post-WWII graphic forms, media analysis, Hong Kong Studies, and Indian English fiction. His creative nonfiction books are the travel-narrative collection refrain and the literary journalism novella cemetery miss you. One day he’ll be a birder. [Cha Profile]