by Aurelio Asiain

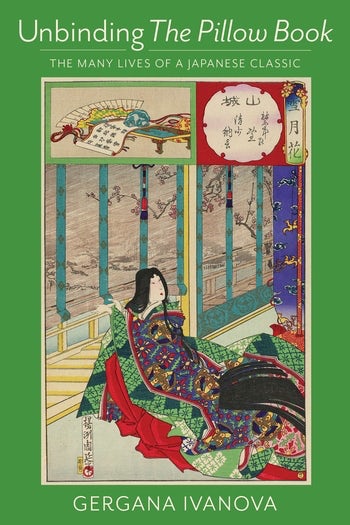

Gergana Ivanova, Unbinding The Pillow Book: The Many Lives of a Japanese Classic, Columbia University Press, 2018. 240 pgs.

What is The Pillow Book? Most people with a background in Japanese culture could provide some of these facts: a Japanese literary classic, written by Sei Shônagon, a lady-in-waiting at the Heian court. It is also certainly the most widely known, read and translated work of the Japanese literary canon. A fascinating book published a few years ago by Valerie Henitiuk, Worlding Sei Shônagon, can prove it: her book is a compilation of forty-eight translations, into fourteen different languages, of The Pillow Book‘s opening passage, arguably the most famous lines in Japanese writing (excluding, of course, a handful of haikus)—and there are possibly a few more translations by now. But, as only happens with great classics, even people who have never opened the book have ideas about it, perhaps because they have read one of several modern adaptations, seen Peter Greenaway’s movie or merely know the title. The word pillow calls up images of intimacy, coziness and eroticism, and it is easy to conceive of the content of a pillow book as something similar to, say, Marquis de Sade’s La philosophie dans le boudoir. The fact that the author of The Pillow Book was a court lady-in-waiting, and the widespread image of the Heian age as close in atmosphere and spirit to eighteenth-century France, adds to this picture. But then we would not be taking into account the fact that the Japanese makura was not a bag of cloth stuffed with feathers, but rather a piece of wood, that the book’s title was most probably not chosen by Sei Shônagon, but by a copyist, or that there is very little eroticism in its pages.

The problem is that we do not know, and probably never will, what the text Sei Shōnagon wrote actually looked like. There is no extant manuscript by her hand, and The Pillow Book has the reputation of being the Japanese literary work with the most significant number of textual variants. Not only the text itself, but the ideas about what kind of text it is, the way it has been edited and divided—as well as the number and nature of its sections (lists or catalogs, essays and diary-like passages)—is basically the result of twentieth-century scholarly work. Before arriving at its present state, the text has undergone endless metamorphosis, and the same can be said of its conception, reception, representation and reconstruction in the mind of readers, editors and translators. These two not parallel but intertwined stories are the subject of Gergana Ivanova’s Unbinding The Pillow Book: The Many Lives of a Japanese Classic. It is a deeply researched and carefully documented account of the book’s history and contains more than a few surprising findings and insights about the evolution of its material, as well as the ideal life of a text, against its contextual reality.

Ivanova’s aim is not to define the closest textual version of a lost original classic, nor to decide its more legitimate readings, but to explore the changing form and literary nature, and therefore the social functions and meanings, that the text has had over time. The account, a compelling argument on the utopic nature of the original and the protean identity of the text, succinctly summarises the complex development of various manuscript lineages, but mostly covers a period of four centuries, from the seventeenth century to modern times; that is to say, the period of the printed and commercial existence of The Pillow Book.

We tend to forget that The Pillow Book was a work commissioned by Empress Teishi, a narrative whose main purpose was to give a lively and attractive account of a triumphant and glamorous court and its cultural and literary sophistication. As it was finished only after the decadence and death of the Empress, the book was first regarded as a funeral prayer and a kind of exorcism and purification, not the chronicle of the mundane it was intended to be. The commissioned exorcist and chronicler happened also to be an agile narrator with a swift, educated mind, a lively spirit and, en somme, a literary genius. As Ivanova writes, “[t]he narrator’s coquettish and self-conscious decorum reveals a strong awareness of the readers’ gaze. The result is a narrative of immediacy and vitality.”

As we learn in Unbinding, The Pillow Book has since its first moments had a changing nature and plural functions, which reflect the literary genius and strong character of its author. Since its conception, and for the next millennium, notions of the book have undergone constant change, including about its literary nature and genre, the place and role of women in society, the character of the author and the place of the work in the literary canon.

The Pillow Book is made of fragments, that is clear. But the exact nature of the extension and limits of each of these fragments and of their division into series and sections has never been fully understood and has been everchanging. The whole collection (although the extension and composition of this “whole” has also been subject to innumerable variations) would successively be seen as a book of personal notes, a disguised diary, a confession, a book of sentences, aphorisms and essays, a miscellany, a zuihitsu (a Japanese genre of floating, diverting, digressing personal essays), a collection of randomly recorded musings, a book of style, an erotic manual and even a literary blog. Some of these notions have been anachronical (blogs of course did not exist in the Heian period, and zuihitsu would not appear until several centuries after its writing). Other notions were more or less imposed upon The Pillow Book, and editors reconfigured and rewrote the book according to them. As a result, the image and valuation of readers evolved.

This rewriting even produced a great number of imitations and parodies, and two of the five chapters of Unbinding explore the transformations the book underwent, reappearing as guide to court life, a guide to the pleasure quarters and then a didactive and formative tool for early modern readers. These two chapters could be seen as an account of the echoes, reflections or phantasmatic reapparitions of the original text. However, in the end, we only have versions and reflections and no definitive original.

As ideas about the book have evolved so have interpretations of the author. Sei Shônagon has been seen as a boastful aristocratic writer, a refined lady with a sense of decorum, a trivial and superficial mind, an arrogant character, a literary genius, an intellectually pretentious woman, a jealous and envious minor writer, a courtesan fixed on love affairs, a model of neo-Confucian morals, a master of style and wit and recently as an example of an independent, strong, empowered woman, a model to modern female writers. Her position in the canon has also changed again and again: an equal or a rival to Murasaki Shikibu, the author of The Tale of Genji, an exceptional talent or a minor, obscure figure.

Of course, all of these metamorphoses reflect social change. The dominance of neo-Confucian scholars in the eighteenth century, the formation of a national literary canon in the same age, the mass proliferation of pornographic literature in the mid-Edo period, the apparition and flourishing of printing houses, the production of books for female readers, the encounter with the West and the shameful vision of Japan as a feminine country, the need to promote a literary nationalism before and after the war, the feminist movement and the appraisal of Western translators and readers have all determined the evolution of The Pillow Book.

The most recent metamorphoses of Sei Shônagon’s classic are Western translations, beginning with the very famous and influential version by Arthur Waley (an extremely reduced and strongly idiosyncratic one), several rewritings by modern Japanese writers and versions for blogs, comics, movies, etc. Gergana Ivanova surely does not take into account all of them, and this would be impossible anyway. As Unbinding The Pillow Book clearly shows, Sei Shônagon’s masterpiece is much bigger than its few pages, because it is an incessantly growing, proliferating, echoing book. This account of many of its innumerable lives is as rigorous as it is fascinating.

![]()

Aurelio Asiain (b. 1960) is a Mexican poet, essayist, publisher and translator. He is a member of the Editorial Board of Letras Libres, one of the most influential literary magazines in the Spanish-speaking world these days. He has been living in Japan for the last seventeen years. He arrived in Tokyo as a diplomat and he now lives in Kyoto. He is a full-time professor at Kansai Gaidai University.