by Michael Ka-chi Cheuk

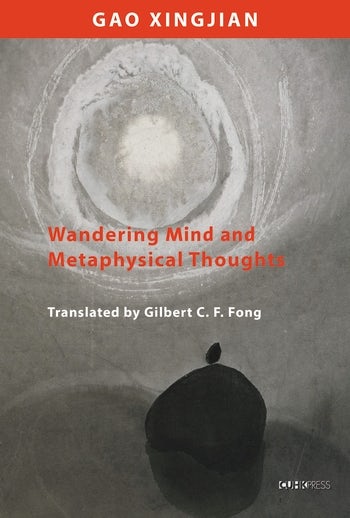

Gao Xingjian (author), Gilbert C. F. Fong (translator), Wandering Mind and Metaphysical Thoughts, The Chinese University Press, 2018. 244 pgs.

As the first Chinese-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (2000), Gao Xingjian is most well-known, even amongst scholars in the field, as a novelist, dramatist and literary critic (often in this particular order). Relatively little critical attention has been cast upon Gao’s endeavors as a painter, film director, translator and poet. Wandering Mind and Metaphysical Thoughts (遊神與玄思) is Gao’s only poetry collection to date. Translated by Gilbert C. F. Fong, this collection of translated poems further fleshes out Gao’s reputation as a cultural polymath. Ink paintings and stills from his films (or what he refers to as “cine-poems”) intersect the poems, evoking a juxtaposition of various media (or what Mabel Lee and Jianmei Liu have categorised as “transmedia”). Fong has been responsible for translating the vast majority of Gao’s output in drama and theatre, including the plays City of the Dead (冥城, 1988), Escape (逃亡, 1990), In Between Life and Death (生死界, 1992), Dialogue and Rebuttal (對話與反詰, 1993) and Snow in August (八月雪, 2000). Fong’s translations are not only fluent, but also effective in conveying Gao’s complex web of cultural influences, which range from Buddhism, Brecht and Beckett, to Shanhaijing, Stanislavski and Sartre. In Wandering Mind and Metaphysical Thoughts, Fong remains consistent in his ability to bridge the cultural gaps for both Chinese-language and non-Chinese language readers. In this review, however, my focus is on Gao’s poetry, as translated by Fong.

Although Gao’s creative production is multifarious in form, his artistic vision of without isms (沒有主義)[i] can be traced in all of his works. Without isms is not a literal rejection or denial of the influence of ideology, but a personal expression of “I am without isms.” This emphasis of expression over isms echoes the description on the back cover of Wandering Mind and Metaphysical Thoughts, which refers to Gao as “poetry incarnate, with the essential purity and density of a good poem.” As the Chinese saying goes, “Literature reflects the person” (文如其人). And those familiar with Gao’s creative works and critical essays can immediately find overlaps of language and theme in his poetry anthology. The self-titled piece “Wandering Mind and Metaphysical Thoughts,” for example, alludes to Gao’s signature symbols and insights: skeleton heads (mortality); God as a frog (meaning of life as open-ended); talking to oneself (the essence of literature) and magic tricks (moral hypocrisy). While the above can be found in his prose work like Soul Mountain and his plays like The Other Shore, they are reimagined in the poetry form. At the heart of ancient Chinese poetry is the revelation of reality, emotion and personality (詩言志). At the same time, its language strictly adheres to the principle of the economy of expression and tone scheme. Gao’s poetry in Chinese, while not necessarily replicating the numerous rules of the Tang regulated verse (近體詩), demonstrate an investment in rhythm and musicality, too.

One of the biggest challenges for Fong, then, is to translate (or in musical terms, transpose) Gao’s rhythm into English. At times, the poems’ rhythm takes a secondary role, and they read more like American beat poetry, particularly when Gao engages in a political tone. The first poem of the anthology, “I Say Hedgehog” (1991) appears in the original Chinese “我說刺蝟” to be a play on the word “saying” in classical Chinese (謂), or spiky, pointy, sharp words. In a dream-like, stream of consciousness way, the poem appears to be intentionally and even self-consciously controversial and provocative. It opens with the lines “Hedgehog / I say / A worm / Flowing slowly.” The contrast between the pointy and lively hedgehog and the slimy worm—as well as the juxtaposition of the actions of the saying and flowing—best contextualises the push and pull of the poem’s tone. On one hand, the work contains sharp words such as “No news / Make one piece” and “Maximum consumption / Men and women are the same / The meaning of equality” are reflective of Gao’s critique of the roles of politics and consumerism in artistic expression. At the same time, Gao adopts a more laidback, indifferent tone with lines like “Childhood is like an old cat / It yawns on the cushion” and “You give / A yawn.” To an extent, “I Say Hedgehog” is reflective of Gao’s awareness of the dangers of self-indulgence or even self-radicalisation. Considering the poem was written in 1991, only two years after the Tiananmen Square Massacre and four years into Gao’s exile in France, it is not surprising to see him harbouring such political observations and sentiments. As much as he is wary of the hypocrisy and restrictions within society, though, he is not interested in engaging in protest through his literary work. Instead, he is more interested in the expression of emotion. And so he showcases both ends of his emotional spectrum, from the sharp and critical (symbolised as a hedgehog) to the lazy and carefree (symbolised as a worm).

Wandering Mind and Metaphysical Thoughts, all in all, is another successful translation of Gao’s creative works. Readers interested in poetry and transmedial expression will find new insights from Gao’s artistic vision and Fong’s translation. Scholars engaged in the study of Gao Xingjian must read this work for a more comprehensive understanding of his oeuvre.

[i] The most common English translation variants of 沒有主義 are “no-ism” and “without isms” with quotation marks. However, I have adopted the translation of without isms (no quotation marks nor hyphenation) to preserve the ambiguity of Gao’s expression.

![]()

Michael Ka-chi Cheuk is Lecturer in English and Comparative Literature at The Open University of Hong Kong. He teaches and writes about Chinese Literature (especially Gao Xingjian) and Popular Culture (especially hip hop).